Distributed Web of Care

Making Space in Online Archives

by Mindy Seu, DWC Artist in Residence

The following is a condensed transcription of a conversational talk given by the author for the Distributed Web of Care workshop series.

My studio experience as a designer focused on interactive installations. While user experience usually connotes people’s movements through an online interface, the phrase could also apply to engagement with physical installations. There are cues that help people navigate a physical environment with a digital layer. This weaving in and out of physical and digital space — which all could be considered an interface — is a space that should motivate discursion rather than display.

This sense of navigation informs how I construct online archives, which I consider a type of activation of a physical site and collection of objects. I would call myself an archival enthusiast, but I’m not a trained archivist, and I would never use the term because it disregards the years of required training. When I first moved to San Francisco, as in all new cities, I sought out used bookstores. Then I fell into a rich library/archival community. While indexes, taxonomy, and categorization have always fascinated me, I was dissatisfied with the use of pre-existing platforms and their navigational structures. Digitized books, regardless of their form or content, were seemingly dumped into templates that used skeuomorphic design (like page turns) and poor UX (like clicking through hundreds of pages).

Image description: L: Jedi Archives, Star Wars: Episode 2, Attack of the Clones // R: Trinity College Library, Dublin”

Image description: L: Jedi Archives, Star Wars: Episode 2, Attack of the Clones // R: Trinity College Library, Dublin”

These are the Jedi archives from Star Wars: Episode 2, Attack of the Clones. It looks like a real library, except these book spines have transmissive light. I see this as a metaphor for how people think about digital or online libraries, transplanting shelves onto the screen with a search field, and not necessarily considering how digital space is different. The original library is based off Trinity College Library in Dublin. Physical libraries have a constraint of nesting books next to each other on shelves. And despite this, libraries have an embedded serendipitous discovery. It’s really easy to get lost in a library. There’s nooks, aisles, hidden corners, shelves nested on top of each other. And that depth, even if it’s linear online, is gone.

The Prelinger Library and Archives in San Francisco offers a fascinating example of a physical space that creates its own unique taxonomy as a reflection of their collected objects. Founded by Megan and Rick Prelinger, the library includes obscure printed ephemera for which Megan created a novel indexing system based on geospatial location. At the front of the aisles you have all the books related to San Francisco, based on theme. The further back you move into the library, you travel through different regions and finally land in outer space.

While the archive exists in physical space, Rick Prelinger offers encouraging insight the digitization of collections. In his Appropriation Manifesto he writes, “If cultural permaculture is our goal, we might think of finding thoughtful ways to represent and re-contextualize old works. So how can we think of alternative methods for digitizing analog materials into a digital interface or a digital screen.” I embraced this as a move away from templatization online and towards the creation of bespoke interfaces that allow for specific viewing conditions for different types of content, much like the geospatial index adopted in his own collection. Rick also states that “mortar is just as historical as bricks, but we only ever talk about the bricks.” Mortar to bricks. We, lay people, can break these histories apart, add or note what is missing, and then rearrange or reform these bricks for our current climate.

Image description: Close-Up: 110 West 40th Street as a domain to note the studio of Herb Lubalin and Ralph Ginzburg in New York ; http://avantgarde.110west40th.com

Image description: Close-Up: 110 West 40th Street as a domain to note the studio of Herb Lubalin and Ralph Ginzburg in New York ; http://avantgarde.110west40th.com

Image description: 110 West 40th Street, New York, present day

Image description: 110 West 40th Street, New York, present day

I created the Avant Garde, Fact, and Eros archival microsites with Jon Gacnik, co-founder of Folder Studio, and Alexander Tochilovsky, curator of the Herb Lubalin Study Center at the Cooper Union. (Note: in the original talk, I explained our decisions for the site interface, redacted here). These publications, created by Ralph Ginzburg and Herb Lubalin in the 1960s-70s, were considered controversial at the time, and led to prison time over a battle with the US Government over obscenity charges.

When we first launched these sites, I was happy that Laurel [Schwulst] noted the domain name 110west40th.com. Sasha [Alexander Tochilovsky] and I had carefully considered other domain names. It didn’t seem right to name it after one of the co-creators. They have a larger body of work, first of all, and these publications are the result of a collaboration in a physical space. We decided to embed this in the naming structure to ground the online sites in the physical site, their studio in Manhattan on 110 West 40th. When Laurel mentioned it, she included a screenshot of Google Maps of the location which has become a shop called Crisp. The domain was able to narrate a bit of the story about where these three iconic publications were born.

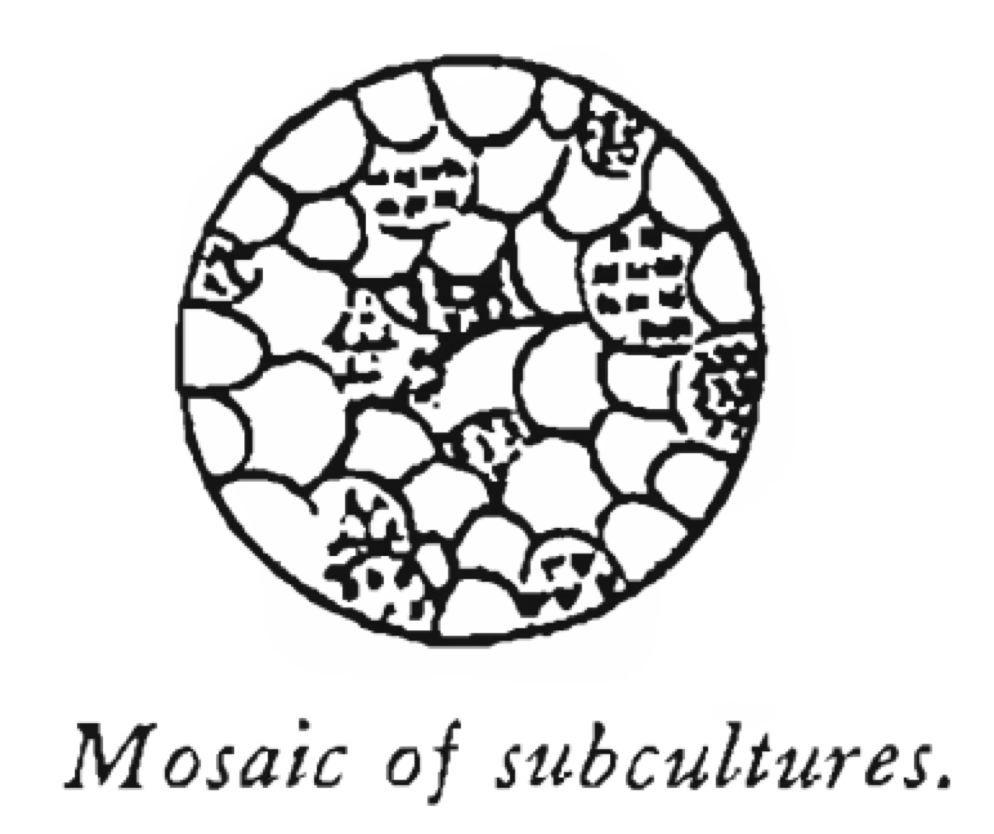

Image description: “Mosaic of Subcultures,” image excerpt from A Pattern Language

Image description: “Mosaic of Subcultures,” image excerpt from A Pattern Language

The chapter “A Mosaic of Subcultures” in A Pattern Language, notes the importance of subcultures, which I find helpful to revisit when designing bespoke interfaces and considering online communities. Instead of homogenizing, or templatizing, visible differences in different communities should be embraced. Moving from one space to another should feel unique, representative of the various cultures, people, identities included. These spaces, however, should be small and nested closely together so you can naturally stumble out of one and into another. You can feel aesthetic or tonal shifts; they are not walled gardens. They are open for others who may not be part of the subculture to visit, embracing inclusivity.

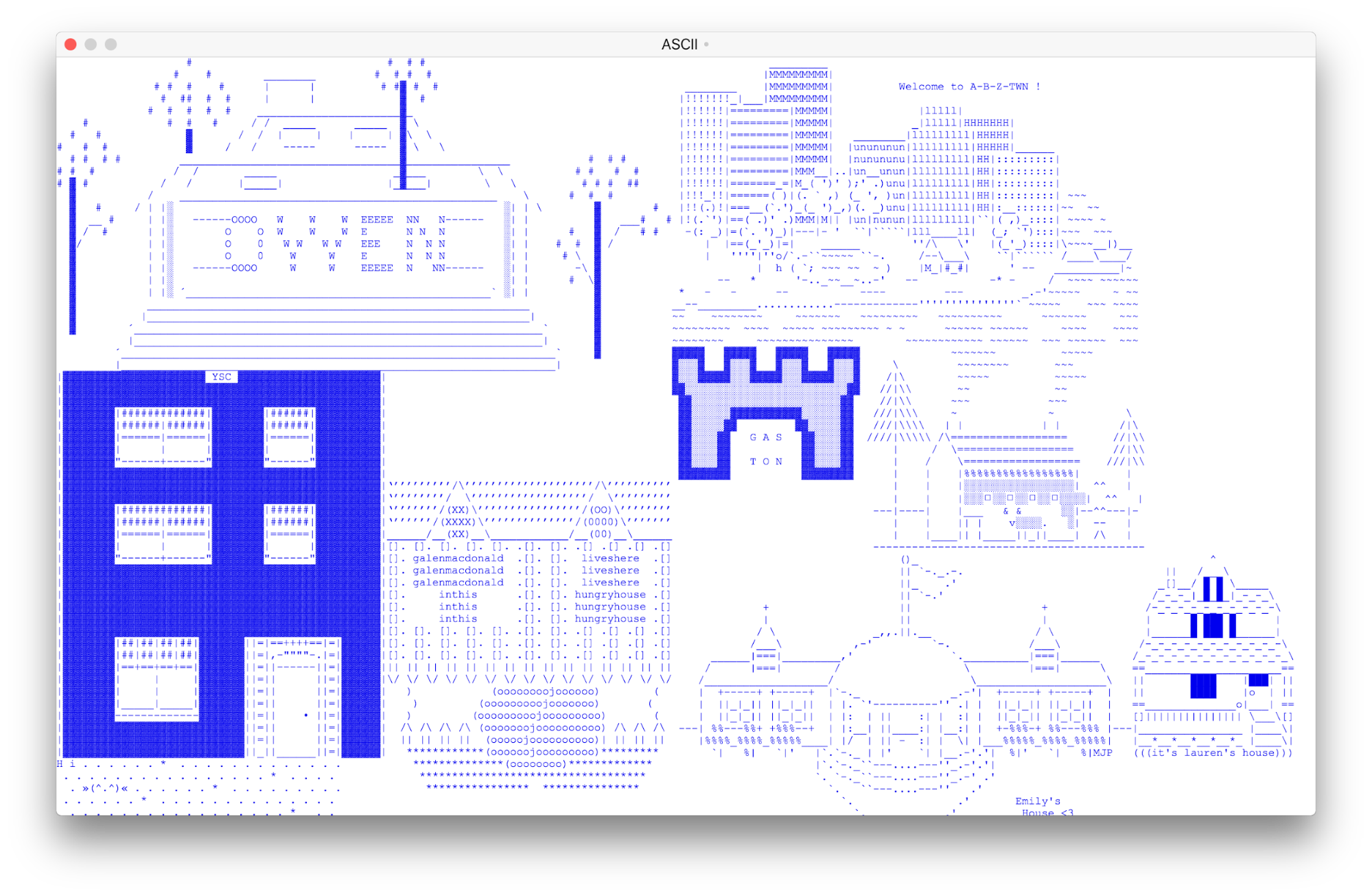

Image description: ASCII Town, A-B-Z-TXT 2017, http://ascii.designforthe.net

Image description: ASCII Town, A-B-Z-TXT 2017, http://ascii.designforthe.net

This chapter motivated a workshop that I created for A-B-Z-TXT 2017. This computational typography summer school is based in Toronto, created by Michèle Champagne, Garry Ing, and Greg Smith. We named it ASCII Town, or A-B-Z-TWN. After a brief introduction to ASCII art, typewriter art, and concrete poetry, the two hour drawing exercise asked how we might still draw with these gridded, constrained systems.

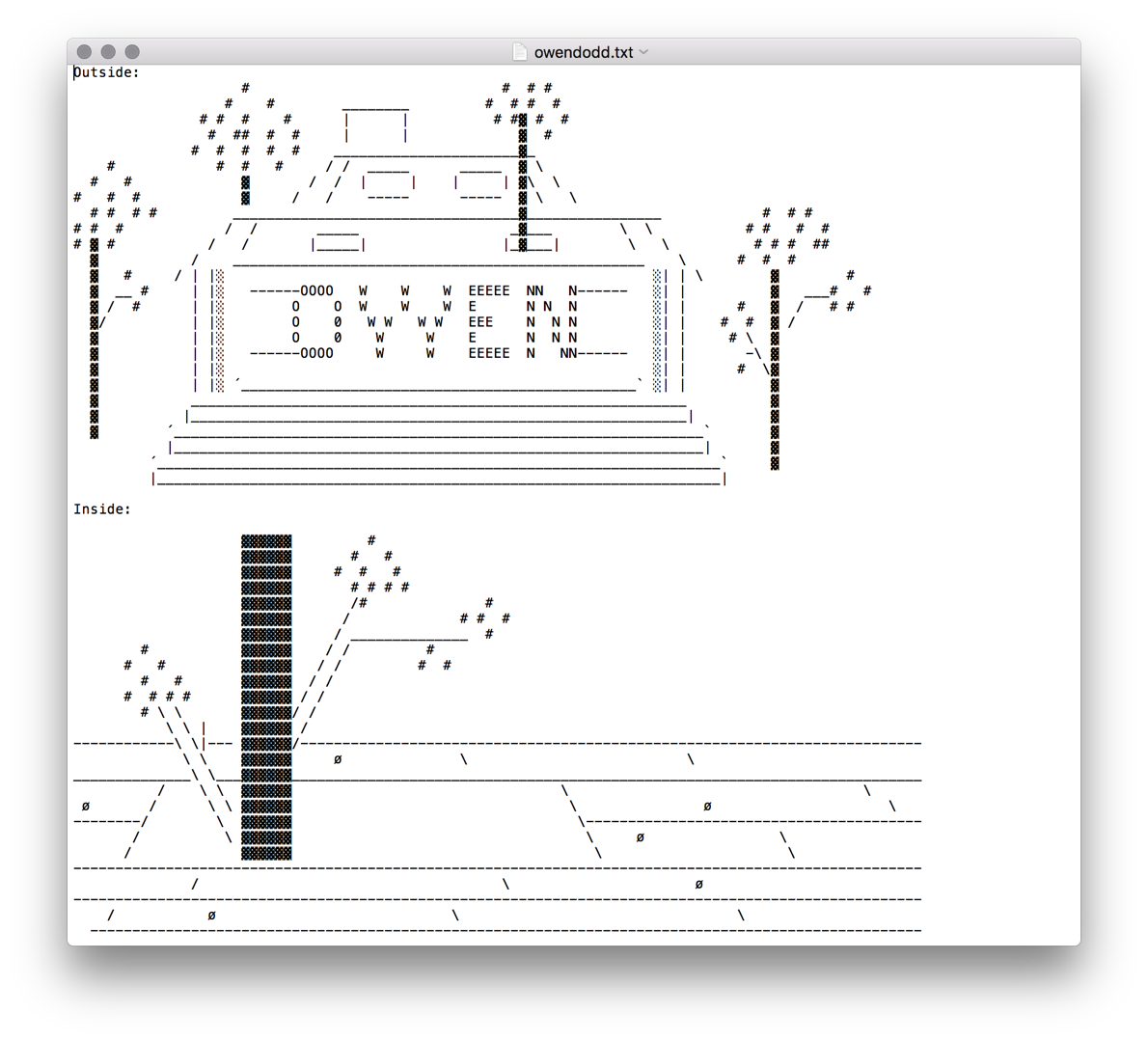

Image description: ASCII Town text file, example by Owen Dodd, 2017

Image description: ASCII Town text file, example by Owen Dodd, 2017

Using a humble text editor, participants drew the exterior of their ‘home’ and a room that others could visit after clicking through. Jon [Gacnik] created a script that would aggregate the exteriors on a group landing page and create detail pages of the interiors using simple labels, ‘Outside:’ and ‘Inside:’ in the text file. The only constraint were these labels and the inclusion of their name somewhere on the exterior. Participants could publish by dragging the file into a communal FTP. ASCII Town asks the user to consider alternative interfaces for online communities, and how this change in interaction might affect how we choose to engage with others in digital spaces.

Image description: Kameelah Rasheed, “On Refusal,” 2016

Image description: Kameelah Rasheed, “On Refusal,” 2016

In an interview on The Creative Independent, Kameelah Rasheed states that archiving our histories is a way to actively engage with the way we move through the world. This recenters us, so we think of ourselves as constructed subjects that come from a long lineage of histories that we can reflect back into our personal archives. I think this idea is crucial, particularly when we consider archiving digital space, and the histories of our own constructions online.

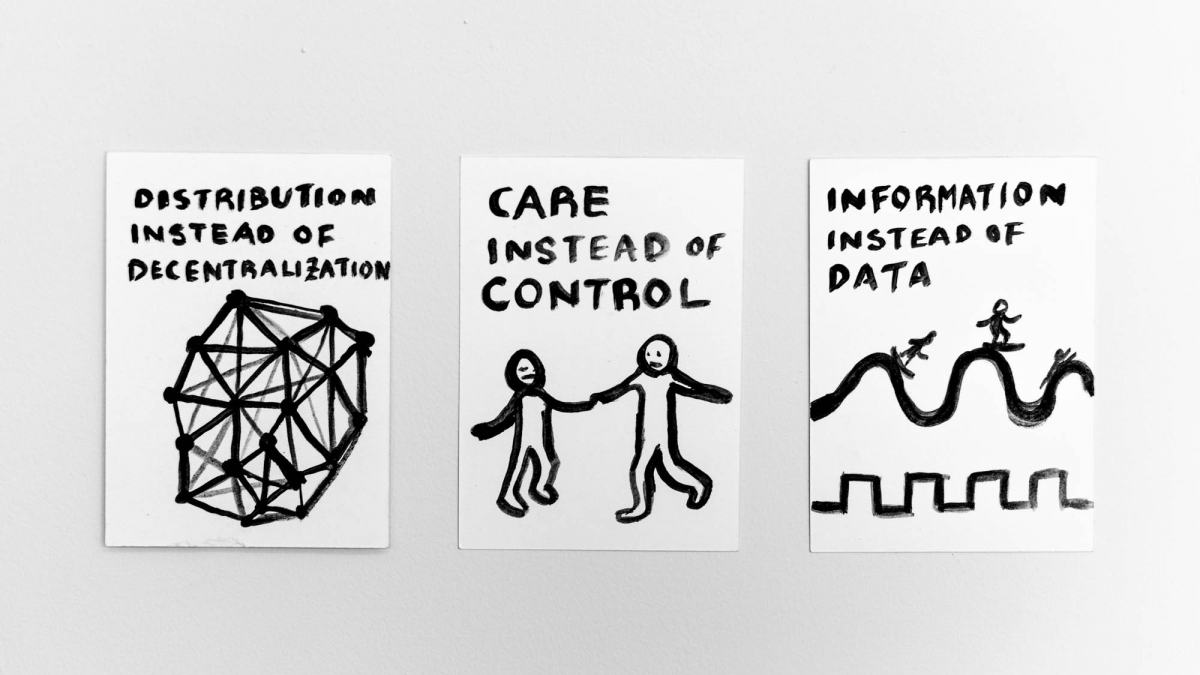

I’m currently a summer fellow at the Internet Archive, co-organizing the Arts Track of the Decentralized Web Summit with Sam Hart. The goal of the Summit at large is to bring together technologists, humanitarians, policy-makers, designers, and artists to discuss the constraints and affordances of various forms of decentralization. For example, with the Dat protocol and Beaker browser, it’s really easy to create and clone a static site or dataset. This feature suggests an invitation to archiving the web, which is noticeably different from ‘scraping’ a site, which is possible but traditionally unauthorized. The Dat and Beaker browser foregrounds cloning and archiving as an essential feature of a decentralized network. Your peers can seed and help host the site. Paul Frazee, a co-founder of Beaker, aptly stated, “Your friends are your data center.” We decide what is valuable, what we want to support, and question what we should read or publish online. While I’m excited about the possibilities, I’m cautious about a technocratic misconception that implementing a decentralized technical or architectural infrastructure will lead to ethical governance or the thoughtful development of culture. How can we reshape online culture as a whole? It’s not like creating a decentralized Facebook will actually make us more connected, even if we do have ownership of our data.

The Arts Track has a conversation series, installations, workshops, and performances that will try to create accessible points of entry, historicize the movement, and consider novel uses of the decentralized web. It’s nice to see some of those people here too. Laurel Schwulst is co-leading a workshop called p2p2p2p. Melanie Hoff, Callil Capuozzo, and a larger team are creating an interactive installation called Distributed Gardens. Yeli Omayeli Arenyeka is co-leading a workshop that prototypes the DWeb with browser extensions. And Taeyoon Choi, with help from Lai Yi Ohlsen, will kick-off the Summit with a large-scale string network performance of Distributed Web of Care.

Q&A, Audio transcript shortened for coherence.

Q: Do you experience tension with making something with a single version or duplication that is reproducible endlessly?

A [Mindy]: Attribution immediately comes to mind. I think it’s fine to duplicate something endlessly if the source material is noted. In some ways, this is what’s great about an open source model. The problem is the difficulty of a precedent that does not include this. I believe it is very important to include this, a clear source or an initial link that is archived to prevent link rot. p2p protocols like dat or platforms like Github allows for this, because you’re cloning something that already exists and a is trail built. Duplication is also important for preservation purposes also. Even at the Internet Archive, where I’m currently a fellow, they have crawlers that click every link and archive every page. They are able to archive the internet once every four months, roughly. It’s only through screenshots, so dynamic content is really hard to capture. But while they have a copy of everything on their servers in the Bay, they have a duplicate in Alexandria and another in an undisclosed location, understandably. The fire at the Library of Alexandria destroyed all of the content it held, and the founder of Internet Archive, Brewster Kahle, will state that this was a key reference for their priority to duplicate.

Q: When you were talking about your Avant Garde work, you mentioned that you wished the rest of the internet could be more like this. Were you trying to emphasis on idiosyncratic archives?

A [Mindy]: By that statement, I meant I would like things to be comprehensive. When people go to an article, do they actually read the whole text? The way it’s laid out now, in these long scrolls with embedded links, with link rot, most don’t read the entirety. In the essay “How We Read: Close, Hyper, Machine,” N. Katherine Hayles writes about how we scan the first few sentences and then your eyes go down. It could be attributed to short term attention span, but I think we can give people more credit than that. It’s built into the reading structure. So by comprehensive, I meant, yes, make the information more robust, but also, what are ways we can explore different ways that encourage comprehension on the screen. I don’t know if Avant Garde is the best way to do that. But I felt that for this publication, we were trying to be very thoughtful about the interface, so people can keep digging. I’d hope that we can be more thoughtful about digestion and comprehension, instead of speed, whatever form that takes.

Q: Could talk about the difference between the library and the archive?

A [Mindy]: Can I throw that to you, Zach [Zach Coble, head of the Digital Scholarship Services at the NYU Libraries]?

A [Zach]: I’m a librarian, and I see libraries as being primarily driven by access. If you want a book or an article or a piece of data, libraries will help you get access to them. Whereas archives are driven by preservation. For that book in the archive that you want to read, every time it’s pulled that off the shelf, the archivist is thinking if there’s some damage that’s happened to the book.

A [Mindy]: I was going to say something similar. I was thinking about inclusivity versus exclusivity. Public libraries are amazing because they’re becoming these new cultural centers, as well as continuing to be a silent space. It is about access. It’s easier to enter a public library rather than an archive — no appointments or white gloves. I feel like there’s a tension between who an archive is for and who created it. It claims to be for community memory, but if it’s inaccessible, it becomes an ethical question about whose memory we are preserving, what we consider valuable, who has the credentials to access it, etc.

A [Taeyoon]: One thing about libraries and archives and their distinction: archives tend to centralize knowledge and power to the institution. Libraries tend to open up and distribute that knowledge and power. While libraries have selection policies, archives tend to be have even more narrow and strict policies about what comes in to the archive. The power of collection leads to preservation, and prioritizing of certain information to last a long time. Take for example, in Los Angeles, The Getty Archive is a very powerful collection of articles and cultural items. It’s a vast resource but it’s not accessible. You need to be a scholar or an authorized person to access the archive. On the other side of town, there’s also a group called Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA), which is an artist-run non-profit organization. LACA takes on a more subversive and grassroots approach to the archive.

A [Mindy]: When I mentioned Irit Rogoff and inherited knowledge, that’s exactly what I meant, The same stories are being told over and over, so certain narratives develop cultural capital. That affects what is preserved and what is fixed in history books. Her “response to conditions,” then, is trying to push against these taught histories and how these smaller histories can be told. A strategy for that is, like Taeyoon mentioned, citizen archives and grassroots spaces.

Q: Earlier, you were talking about the difference between digital and physical archives and getting lost in physical spaces. In your work, have you thought about how developers and designers can help users have a serendipitous experience like that online?

A [Mindy]: If you can make your own website, even if it’s ugly and messy, maybe we can reframe it as ugly beautiful. It does give you a lot of power when you see something that you’ve made living in the world. It doesn’t have to be perfect. Does it really matter if something is responsive or snapped to a grid? Maybe that works well for some things but not necessarily for personal voice.

Readings for the skillshare

- A Pattern Language, “A Mosaic of Subcultures” by Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein

- Turning, “Education” by Irit Rogoff

- Kameelah Rasheed on research and archiving by Kameelah Rasheed and Brandon Stosuy

- Archives excerpt by Dennis Yi Tenen

- Appropriation: is it finished? A Manifesto by Rick Prelinger

Credits

This essay is based on a skillshare by Mindy Seu on July 8.2018 at the Ace Hotel New York. It’s been edited by Shira Feldman and published on February 8, 2019.

Mindy Seu

Mindy Seu is a designer and educator. She is currently a student in Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, where her research focuses on digital archives UI and methods of digitization. Formerly, she was a designer at 2x4 and instructor for Interactive 2 at California College of the Arts.

Distributed Web of Care is an initiative to code to care and code carefully.

The project imagines the future of the internet and consider what care means for a technologically-oriented future. The project focuses on personhood in relation to accessibility, identity, and the environment, with the intention of creating a distributed future that’s built with trust and care, where diverse communities are prioritized and supported.

The project is composed of collaborations, educational resources, skillshares, an editorial platform, and performance. Announcements and documentation are hosted on this site, as well as essays by select artists, technologists, and activists.

-

Jun 30, 2024

에콜로지컬 퓨쳐스

-

Jun 30, 2024

Ecological Futures

-

Nov 26, 2022

P2P Residency Berlin

-

Jan 4, 2022

garden.local

-

Jun 7, 2020

Community Over Commodity

-

Mar 18, 2020

Oddkins

-

Oct 10, 2019

New Merchandise

-

Aug 10, 2019

Announcing Decentralized Networks Workshop

-

May 24, 2019

On Stewardship

-

May 23, 2019

Movement Scores

-

May 4, 2019

Who Owns the Stars: The Trouble with Urbit

-

May 1, 2019

Announcing WYFY School with BUFU

-

Mar 5, 2019

Announcing Lecture Performance at the Whitney Museum

-

Feb 25, 2019

Announcing Call for Deaf or Disabled Stewards

-

Feb 7, 2019

Making Space in Online Archives

-

Jan 29, 2019

Accessibility Dreams

-

Jan 28, 2019

Creative Self Publishing

-

Jan 11, 2019

Racial Justice in the Distributed Web

-

Dec 29, 2018

Announcing LACA Residency

-

Dec 28, 2018

Announcing DWC at Code Societies

-

Dec 21, 2018

Building a Museum 353 Years in the Future

-

Sep 11, 2018

Finding Intimacy within Black Feminist Criticism

-

Jul 26, 2018

still stuck with words

-

Jul 26, 2018

Distributed Dance Floor

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing Skillshares: Peers in Practice

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing the Distributed Web of Care Party

-

Jun 27, 2018

Communities and New Infrastructures

-

Jun 27, 2018

New Gardens

-

May 20, 2018

Announcing Summer 2018 Fellows

-

Apr 28, 2018

DWC Merchandise: Care Shirt & Hoodie

-

Apr 27, 2018

Announcing Artists in Residence at Ace Hotel New York

-

Apr 18, 2018

Documentation: Ethics and Archiving the Web

-

Apr 18, 2018

Call for Fellows and Stewards

-

Apr 17, 2018

Code of Conduct

-

Mar 18, 2018

About

-

Distributed Web of Care