Distributed Web of Care

Building a Museum 353 Years in the Future

by Ari Melenciano, DWC Artist in Residence

Originally posted on Ari’s blog on July 2, 2018, reposted on December 26, 2018 with permission.

An exploration on the eradication of racial oppression in future times, through speculative design and futuristic ideating of a utopian city and society called, Afrotopolis.

We’re fighting for a better future. But what does that future actually look like? What will it feel like when Black Americans are no longer living in intensely toxic situations that have been carefully designed for White American gain? What type of art would Black artists be able to make when we no longer have to simultaneously fulfill our artistic needs while also fighting to push our culture forward? What will happen when automation entirely wipes out the proletariat and a war on current societal standards have erupted? This is a speculative exploration on the future through a Blackness lens on the psycho-geography of afro-futurism and societal design.

Part 1

As one of the Ace Hotel in New York City Artist-In-Residence (curated by Taeyoon Choi), I began my 24 hour residency by presenting a skillshare, where there were about 15 participants, a mix of artists, designers, activists and engineers, who signed up to participate. The presentation started with a survey of my past works from building cameras, to creating a new media arts, culture and technology festival called Afrotectopia, to the data visualizations I’ve built that analyze the relationships between music video cinematography with the rhetoric and sentiments within lyrics. After the survey of past works, I dived into more recent thoughts on the structure of America and the ways these structures have been identified and highlighted within different pieces of art.

“Let’s Talk About Race” Oprah Magazine | Photographer: Chris Buck

This survey included monumental work photographed by Chris Buck for the Oprah Magazine (May 2017) that highlights stereotypes and offers an opportunity to reimagine, by reversing them — as well as the hyper-surveillance of Black communities by police, that Jay Z communicates in his Marcy Me music video.

Marcy Me — Jay Z (music video screenshots)

My presentation then shifted to the job of activists and the feelings of being “jaded”. Which, inevitably becomes a sort of Activism Exhaust.

Activism Exhaust is the feeling of being “low on fuel” after having exercised various forms of activism for extensive periods of time. It is a frustration that occurs when success and progress within the fights for civil human rights is difficult to identify through standard success metrics. Thankfully, through several conversations with friends and colleagues— I was able to experience necessary paradigm shifts to reinvigorate my sense of possibilities within my own activism work. One included a conversation with Rashida Richardson, a lawyer that spoke on the Black Resistance White Algorithms panel at Afrotectopia. In brainstorming possible solutions for the advancement of Black society, she noted how our fight as activists was missing a key element: a constructive and well-researched idea of the future.

Illustration by Ari Melenciano

Leaving that conversation inspired me to begin my future activist work by defining an ideal place in time of racial equity and then move backward, creating a series of steps on how to get to this utopia. My thinking shifted from “how do we create a more equitable future for the Black society?” to, “what does an ideal society for Black people look like, and what steps would need to be taken to get there?”

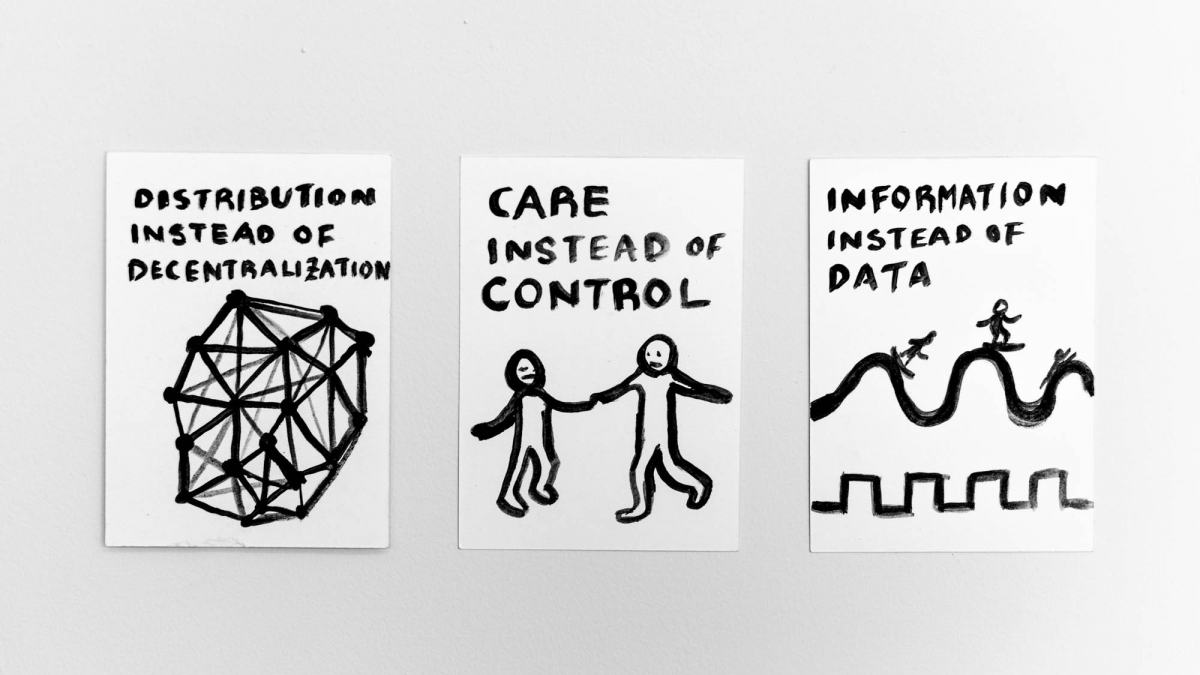

In this new paradigm, I also spent more time researching digital carceral infrastructure (Jackie Wang’s Carceral Capitalism has become a new favorite), technological automation’s effect on the proletariat, geo-political activism, and different forms of speculative design. Through this lens, I embarked on a more intense analysis of current societal structures, beginning with capitalism and decentralized vs. centralized forms of access — to eventually building my own society and vision for the future, called Afrotopolis.

This new paradigm allowed me to dive deeper into an older idea of mine titled, The Afronet — which would serve as a key component in the development of Afrotopolis.

Black culture is Black society’s most lucrative export. It is also currently the world’s most profitable culture. Yet, the Black producers of this culture are barely receiving any of the monetary gains, while those that do have the capital to invest in the exploitation of Black culture for capital gain, which are predominately White men, are the only ones truly able to profit off of the culture. It is a cycle of cultural exploitation through racial expropriation via culture vultures funded by venture capitalists who’s ability to exist is off of the backs of poor, Black citizens. So, what sort of tool could be developed to no longer give access to Black culture to the people that do not quintessentially understand it or its history? What sort of system could be developed so that Black culture producers are the only ones profiting off of their creations (or at least profiting the most)? How would America have been able to operate differently if the ability to access a youtube video of Jay Z first required the ability to pass a series of tests analyzing one’s comprehension of Blackness and racial politics? Ideally, the development of The Afronet, would inspire new forms of radical digital activism for other cultures — similar to how the construction and practices of the Black Panther Party inspired the Chicano Brown Berets and Puerto Rican Young Lords.

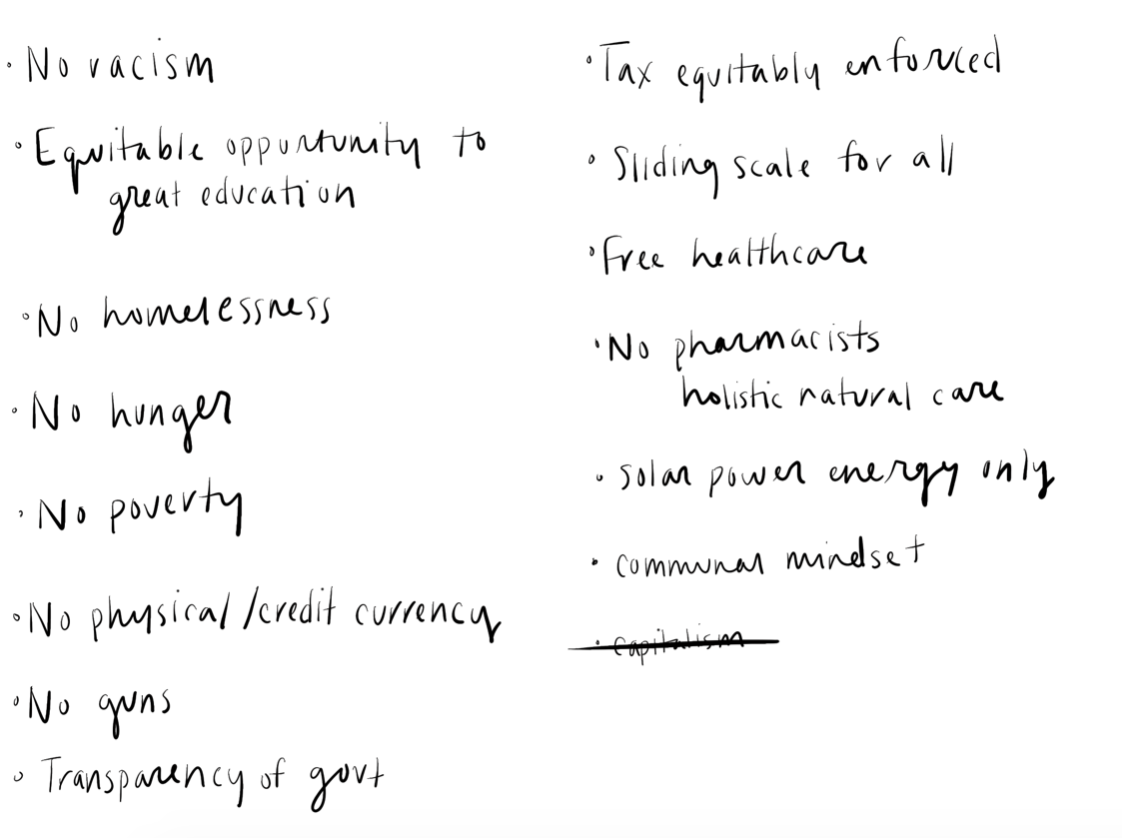

In this exploration and development of Afrotopolis, I established a series of common values.

Values of Afrotopolis, Illustration by Ari Melenciano

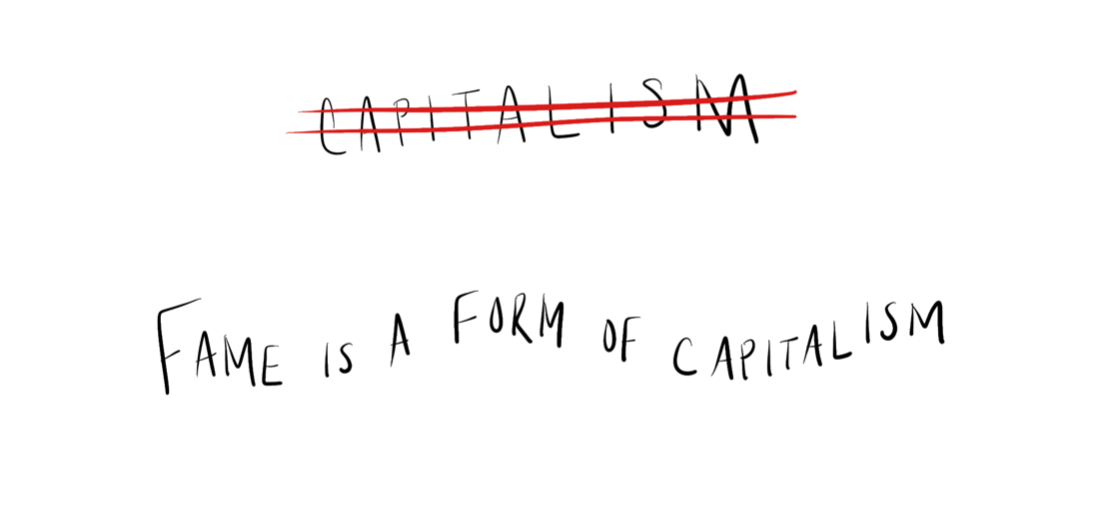

My study progressed to focus on what has currently and previously occurred in various societies around the world — that I feel should be dismantled for the sake of mankind. I began exploring how social media introduces and exercises a form of social capital, and how social media has introduced hyper levels of individualism that may be doing more harm than good. As opposed to collective contribution to a communal society, we are finding odd situations occur — like non-profits of similar objectives competing for the same pool of money (maybe one entity feels that they are more equipped to handle the job than the other — which is understandable, but maybe one group aims for a larger amount of power — which requires a sort of hypocritical oppression of the other) or bureaucracy getting in the way of societal advancement that would better the lives of millions. This ties to a sort of greed (which I believe is current society’s greatest flaw) that is produced by capitalism. Social media has bred a new form of individualism that makes faces and identity a form of currency. It is a type of individualism that is intensely competitive and one that establishes new forms of digital oppression.

This form of individualism’s most common objective is fame. Fame, i’ve found, is strongly tied to capitalism. What if, in this new society of Afrotopolis, individualism was dismantled and replaced with communal strategy for holistic cultural advancement of all? Would that require the elimination of capitalism? I’m currently not finding a way that fame (in it’s current framework) could succeed without capitalism.

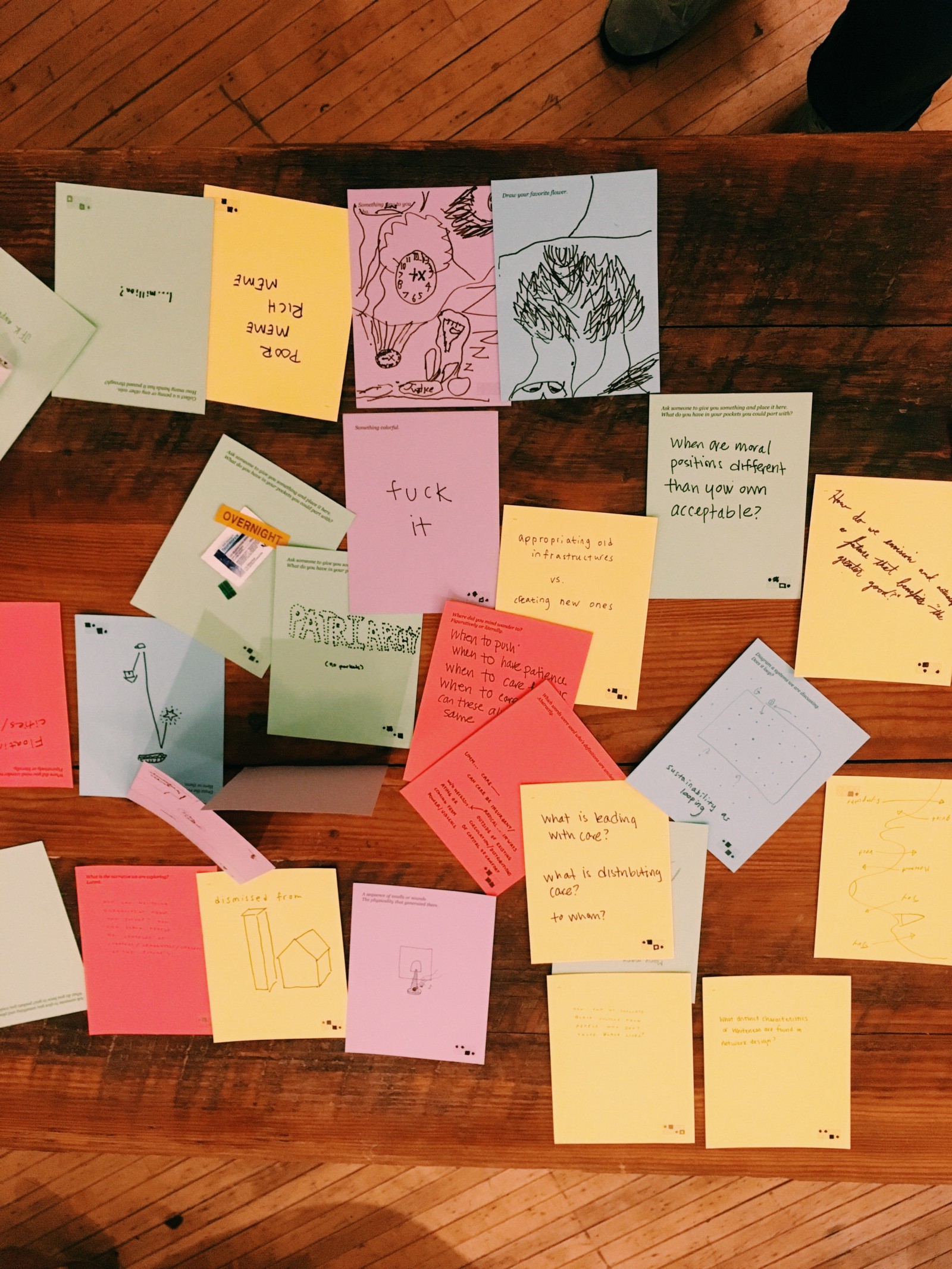

These ideas were presented in the skillshare part of the Distributed Web of Care residency. They were followed by an open discussion on afrofuturism, socialism, Blackness, hegemony, decentralized web structures and more — held both inside the Ace Hotel’s Boardroom and in Madison Square Park.

Participants of DWC Skillshare #1 Photo by Ari Melenciano

(Following photos taken by Taeyoon Choi, and DWC Fellows Cleo Miao and Callil Capuozzo)

Part II

The second part of the Distributed Web of Care residency, was a speculative design practice and social experiment.

In returning to this idea of Activism Exhaust, I wanted to give a few of my friends and I a chance to explore a future where we no longer have to be activists of racial oppresion. This exploration tied back to my questions at the beginning of this essay:

What will it feel like when Black Americans are no longer living in intensely toxic situations that have been carefully designed for White American gain? What type of art would Black artists be able to make when we no longer have to simultaneously fulfill our artistic needs while also fighting to push our culture forward? What will happen when automation entirely wipes out the proletariat and a war on current societal standards have erupted?

To speculatively answer these questions, I designed a space for my friends and I to enter and explore with deep imagination, for the night.

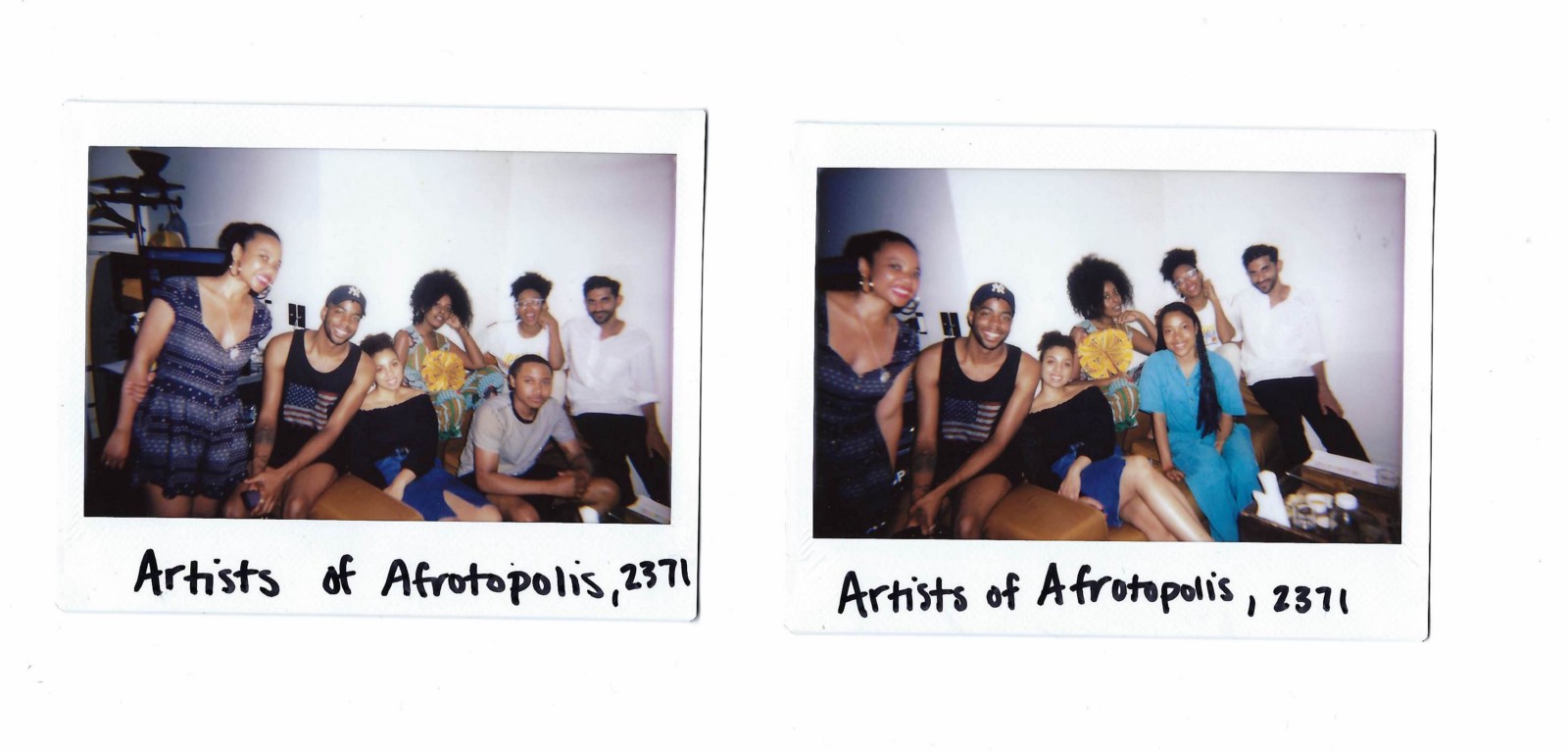

Participants of El Museo de Afrotopolis

Instant Photos of the Artists of Afrotopolis, 2371

Illustration by Ari Melenciano

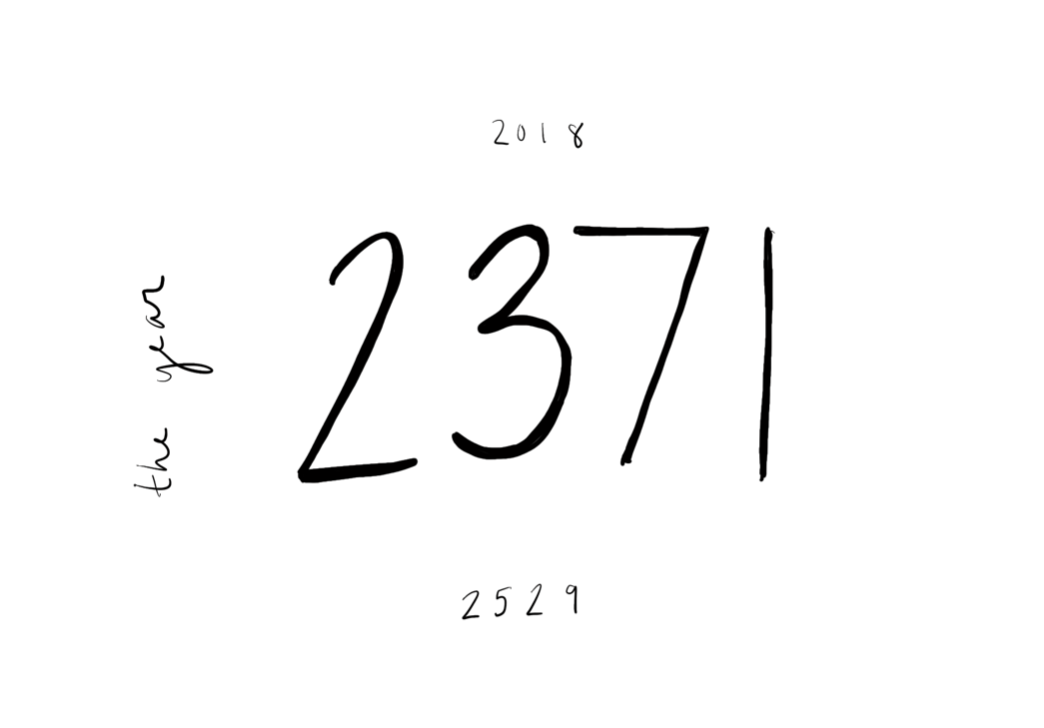

We entered into the year, 2371.

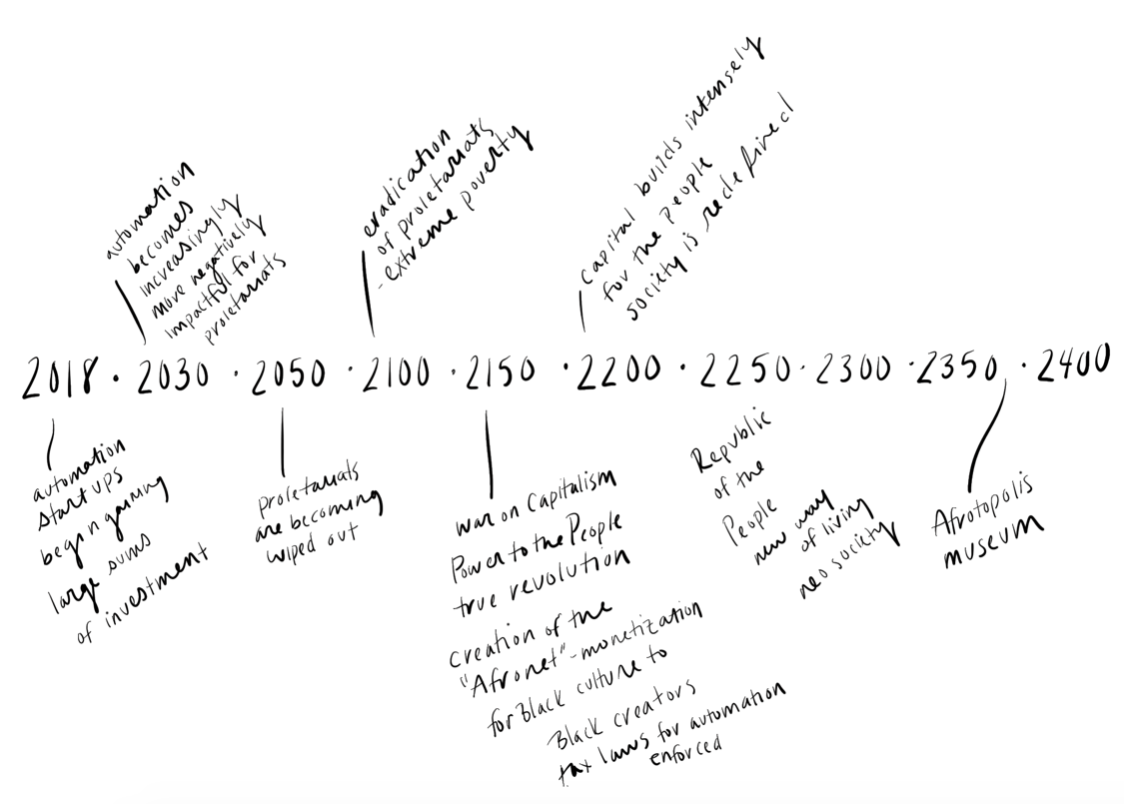

In the timeline of events:

By 2100, the massive amounts of investments and research that were being poured into the advancements of technological automation (machine learning and artificial intelligence) had completely wiped out the proletariat — producing an extreme level of poverty, exponentially greater than ever experienced before. As introduced by Walter Mosley in his short read, Folding the Read into the Black, I began to further explore the possibility of AI technology developers being taxed for their productions by metrics of the human labor it has eradicated. By 2150, this taxation on AI would be heavily enforced in attempt to supplement the displacement of the previously existing working class. By 2150, there is a war on capitalism and a true Power to the People Revolution, where the oppressed people of the entire world would unify in the redistribution of access to sustainable living. This would also be the era when the Afronet has fully infiltrated the centralized web network — creating immense amounts of capital for the Black society, right before capitalism is completely destroyed. By 2250, capitalism no longer exists, the tax on automation has eliminated classism by providing all with a bountiful amount of resources to sustain a desired life. Afrotopolis is considered a true Republic of The People, and has completely redefined societal standards — reflecting the Afrotopolis values aforementioned.

In this speculative design experience, the idea was that we had traveled to the year 2371, which was generations further into the future from the war on capitalism and the true Power to the People revolution — leaving the current society in opportunity to relish in this new world of equality in regards to civil rights, distribution of power, and access. Humans alive in the year of 2371 were 353 years removed from the tribulations of today, and deeply immersed in a world that no longer required them to be activists of racial advancement.

With this context, each participant of the night was then given an entirely new identity and told that they have been invited by the archivists of El Museo de Afrotopolis, to contribute their art into this museum. These moments throughout the experience were possibly the most disorienting as each person in the room currently (today in 2018) creates art that somehow stems from their racial identity, and ways that it oppresses their agency. How would it feel to no longer have that responsibility, but to instead be able to create purely for art’s sake? Would the art we create be purely for art’s sake or would we have other subjects to focus on? We started off with a 45 minute long conversation exploring the possibilities of our new realities, over a group dinner.

We then spent the next 30 minutes creating art as we further imagined where we’d artistically communicate from, with this new reality.

Tsige (Zen) capturing for her film

Artists at work

Artists at work

Roxana (Migo) at work

Tsige (Zen) at work

We then spent the next 30 minutes sharing our work with one another.

El Museo de Afrotopolis Archive

Tao Leigh Goffe

Tao, re-identified as Pumoash, was a dancer, dance coach and urban designer who also enjoyed traveling, going to broadways and baking sweets. Pumoash studied historical games, including Dance Dance Revolution to create, “Dance Dance Revolution Architecture as dancing 2150 Power to the People Revolution as dance dance as revolution urban design + dance.”

Terrell

Terrell, re-identified as Yayot, was a digital media artist and painter who professionally practiced computer science and bartending and also enjoyed meditating, drawing and problem solving, in their free time. Yayot created “an interactive tool to compile stories of local customers to capture the stories behind bar visits. Customers tell, bar captures, the tech appropriates data into viable info for population.”

Tsige

Tsige, re-identified as Zen, was a writer, photographer, and film director who enjoyed gardening, stargazing and debating on politics. Zen made a “meditation with intimacy/love by lil B.”

Tsige, re-identified as Zen, was a writer, photographer, and film director who enjoyed gardening, stargazing and debating on politics. Zen made a “meditation with intimacy/love by lil B.”

Roxana Santana

Roxana, re-identified as Migo, was a video artist, podcaster, and florist who also enjoyed poetry, drawing flowers, and reading about astronomy. Migo explored botanism and how the creation of a “traditional flower … transitions into freedom of growth.”

Finding Home: An Immersive re-discovery of Identity Through Flavor

Cover of recipe book

Contents of recipe book

Sandra, re-identified as Oeii, was a writer and journalist for the Afrotropolis Times who was also passionate about the bioengineering of fruits and international recipes. In describing her work, she said, “Art is a written connection of questions and quotes around identity, memory, ancestry, and food. Also, recipes.”

Romil

Romil, re-identified as Nellano, was a street artist, public sculpture artist and carpenter who enjoyed sculpting with soap bars and watching indie films. For his piece, “Population Projection”, Nellano created an “LED wall with wooden dials. Dials change societal variables to project impacts on population. LED wall also shows historical population changes over time.”

C. Lee

Twiobi, creator of time travel robe, exhibits operation as Migo wears the robe.

Christopher, re-identified as Twiobi, was a seamstress and fashion model who enjoyed collecting stamps and other historical artifacts, hiking and mixing music. Twiobi created a “Metallic time-travel robe with audio clips over the 350 year period when wearer puts on the robe.”

Ari

Illustrated Cake (before)

Illustrated Cake (after)

Woman 001

Woman 002

Ari (me), re-identified as Mirable, was a cake designer, physicist and molecular scientist who enjoyed cycling, reading vintage sci-fi novels and painting portraits of animals. Through a “series of image manipulations”, Mirable used “part one [to create] illustrations of cakes .. morphed into other objects of abstract form” and “part two [consisted of] photos of Black women of the 21st century … gone through a series of digital distortions — changing their hair and appearance as they attempted to fit into White notions of beauty.”

The night brought incredible insight and new alterations to current paradigms of thought. We meditated heavily on thoughts of what the necessary levels of maturity might be needed to experience a night like this (Terrell), how our place in the world changes when we thinking of future societies being descendants of our actions of today (Tsige), what freedom actually means, and what Blackness means absent of oppression.

None of the audio from the night was recorded, to create a genuine sense of liberty and freedom within our creativity, as well as security and safety within our expression.

The following morning was spent documenting the night.

Ari (me) in front of the hotel mirror

Entry in Ace AIR sign book

Photos from Afrotopolis

Contribution to the Ace AIR archive

Thank you, Ace Hotel, for featuring my work on your TVS.

I left the hotel inspired to continue developing and growing the idea of Afrotopolis, with more minds to collaborate with.

Thank you Taeyoon Choi, for the opportunity to explore art and technology in my first artist residency. Thank you, Ace Hotel New York City, for the great hospitality. And thank you Christopher, Terrell, Sandra, Tsige, Tao, Romil, and Roxana for joining me in a night of futuristic and experimental thinking.

There will be more skillshares with other Artists in Residence in July and The Distributed Web of Care Party will be held at the Liberty Hall at the Ace Hotel New York on July 29th from 3–7pm.

Credits

This essay has been edited by Shira Feldman and published on December 21st, 2018.

Ari Melenciano is a Brooklyn-based interdisciplinary artist, designer, creative technologist and activist. She recently graduated from NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Graduate Program (ITP) and will be returning to NYU ITP to be a researcher — focusing on imaginative uses of technology, digital carceral infrastructure, archiving Blackness in new media, and digital activism efforts. Learn more about her work at www.ariciano.com. She can also be found on twitter (@ aricianoo) and instagram (@ ariciano).

Distributed Web of Care is an initiative to code to care and code carefully.

The project imagines the future of the internet and consider what care means for a technologically-oriented future. The project focuses on personhood in relation to accessibility, identity, and the environment, with the intention of creating a distributed future that’s built with trust and care, where diverse communities are prioritized and supported.

The project is composed of collaborations, educational resources, skillshares, an editorial platform, and performance. Announcements and documentation are hosted on this site, as well as essays by select artists, technologists, and activists.

-

Jun 30, 2024

에콜로지컬 퓨쳐스

-

Jun 30, 2024

Ecological Futures

-

Nov 26, 2022

P2P Residency Berlin

-

Jan 4, 2022

garden.local

-

Jun 7, 2020

Community Over Commodity

-

Mar 18, 2020

Oddkins

-

Oct 10, 2019

New Merchandise

-

Aug 10, 2019

Announcing Decentralized Networks Workshop

-

May 24, 2019

On Stewardship

-

May 23, 2019

Movement Scores

-

May 4, 2019

Who Owns the Stars: The Trouble with Urbit

-

May 1, 2019

Announcing WYFY School with BUFU

-

Mar 5, 2019

Announcing Lecture Performance at the Whitney Museum

-

Feb 25, 2019

Announcing Call for Deaf or Disabled Stewards

-

Feb 7, 2019

Making Space in Online Archives

-

Jan 29, 2019

Accessibility Dreams

-

Jan 28, 2019

Creative Self Publishing

-

Jan 11, 2019

Racial Justice in the Distributed Web

-

Dec 29, 2018

Announcing LACA Residency

-

Dec 28, 2018

Announcing DWC at Code Societies

-

Dec 21, 2018

Building a Museum 353 Years in the Future

-

Sep 11, 2018

Finding Intimacy within Black Feminist Criticism

-

Jul 26, 2018

still stuck with words

-

Jul 26, 2018

Distributed Dance Floor

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing Skillshares: Peers in Practice

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing the Distributed Web of Care Party

-

Jun 27, 2018

Communities and New Infrastructures

-

Jun 27, 2018

New Gardens

-

May 20, 2018

Announcing Summer 2018 Fellows

-

Apr 28, 2018

DWC Merchandise: Care Shirt & Hoodie

-

Apr 27, 2018

Announcing Artists in Residence at Ace Hotel New York

-

Apr 18, 2018

Documentation: Ethics and Archiving the Web

-

Apr 18, 2018

Call for Fellows and Stewards

-

Apr 17, 2018

Code of Conduct

-

Mar 18, 2018

About

-

Distributed Web of Care