Distributed Web of Care

On Stewardship

by Jerron Herman

Attending. Attending. Attending. As you prepare to demonstrate your prowess, attend to the ones here. If ego plays a part, you are doomed. Also, you’ve got something to offer.

Image description: Jerron Herman takes the floor to guide participants through movement exercises, exploring the various states a network can be. He stands in all black in the center of the room, with one arm raised and the other cradling his torso. The stewards in DWC shirts sit on the ground around him, in front of the audience seating. He introduces himself as “a disabled dancer with an interest in bridging disparate things together, hence computational theory and dance.” Jerron tells the audience that together we’ll be going through “experiences of taking the networks - centralized, decentralized, and distributed into our bodies.” He states his intent of using the disability experience to deepen our communal understanding of care, offering the idea of “disability genius,” as a singularly distinct output a disabled folk will communicate in a new way of working.

Sometimes, you have to encourage yourself.

Contributing to the Distributed Web of Care event at The Whitney Museum was a real-time activation of collaboration for me, one that still reverberates across my professional career in impressionable ways. In it I learned the compelling truth of humility and the liberation of stewardship. When developing a solo practice, it is very common to take on everything and any delegation is done begrudgingly, when time or energy is scarce. One never seeks help with full capacity. Yet, as I entered the first rehearsal of DWC, I felt the unmistakable dizziness of assistance, of support. In addition to the DWC Stewards, a steering collective of artists and engineers, the space contained a scribe, multiple rooms to play, smart volunteers, and snacks. These are considered luxuries in other contexts whereas here it was commonplace. This context set me up to imbibe on critical thought that was not based on exasperation or exhaustion; this was an easy task, the rigorous part was yet to come.

I’m still processing the series of events: invitation to interpret distributed networks via movement, good first rehearsal, dismal tech rehearsal, formative discussion, last minute rehearsal, magical activation. Across these events I felt my usual tension to perform melt to the simmering sensation of release, an incomprehensible comfort with unknowing and a growing delight in play.

How was I to know Distributed Web of Care was a metaphor?

Humility is possibly the last emotion before a breakthrough. With humility, one is absolved of their need to strive, instead becoming present, able to mindfully solve problems without needing perfection. I believed, as a first-time collaborator to the project, that I didn’t know how to interpret this vast ontological concept, this new ideology, that was distributed web of care. I began to regurgitate Taeyoon and Cori Kresge’s original formula, thinking no one would see me slipping if I just repurposed a found object. Yet, it was evident that in denying the activation of my voice, even the template fell flat for this event. It could not be regurgitated. But I had other rehearsals and jobs where I was responsible for grants and donors, not to mention my own self-care. It could not be regurgitated. Confronted with this truth, I finally asked for clarity, a brainstorm, another way in.

It was after our tech rehearsal at the Whitney. You know that feeling that something’s not right, but we’re all smiling through? I was so bemused by the DWC collaborators’ generosity and optimism that I didn’t want to seem confused or possibly laborious because I needed some extra help. We’re all doing our part. But I remember approaching Taeyoon, understanding Taeyoon, to reveal that I was lacking some grounded identity. Reassuring, he suggested a phone call the next day wherein we collaborated on the format. Clarity happened with the introduction of myself in the web of care. I thought, what am I curious about? The answer(s) were how this activity would expand relationships and get us moving, period. With a new breath, and my intention on the event restored, I made a movement.

It started with the movement phrase. It was deliciously simple and yet very “of my body” which made me feel more comfortable about facilitation. I tried out the phrase - mostly torso and hands to mitigate any separation for those seated or otherwise less mobile - in the communal holding space at The Whitney in plainview of the stewards.

You can play the facilitator or actually facilitate. I have internalized this unnecessary pressure as the facilitator to be flawless in the presence of audience or aids, but do not have a critical framework for failure. So, I’m simply nervous to fail and that’s all. In this experiment I spent too much time worrying rather than enjoying. The stewards were never supposed to be my lemmings, but my peers; us working together. I finally saw that.

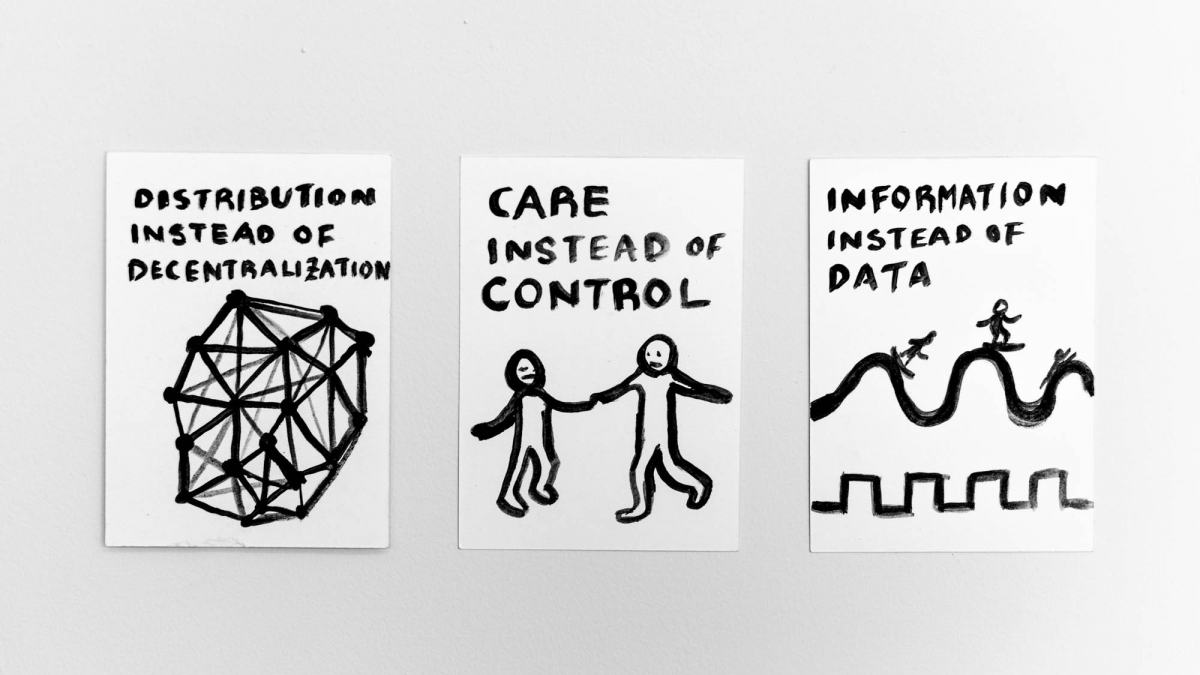

I began to facilitate when I simplified what would occur and what would be the parts of entry for the stewards. From another, still complicated but clearer, rehearsal I set a plan and continually asked for agreement from the group. We would explicitly use the three totems of the web of care, “centralized”, “decentralized”, “distributed” and refer to our individual and collective bodies as the metaphor. So people would first feel their own network, then relate to multiple networks through extended tethering activities, like creating smaller circles of networks. The stewards were going to hold the space for others to explore and be centering figures, mediating my instructions.

Image description: Jerron guides the audience through the first movement exercise: recognizing and feeling our own individual sense of network before we start to experience others’. Participants and stewards have their arm raised in various directions, instructed by Jerron to “take your right arm and extend it out in a safe position, maybe in front, maybe behind, maybe above you.” He continues to guide, “move it [your arm] around a little bit in a circular motion, but keeping the tension of the arm as straight or as tense as it can be.” After being led through other exercises of feeling our own bodies, Jerron states: “that’s your network. Your own individual network”

There was an extraordinary mutual learning moment in the midst of us creating smaller networks where one steward, Lori Hepner, disclosed she felt particularly stressed about the activity involving coordinated movement within the “decentralized” section. In this section, stewards and participants would take my guided choreography into smaller networks to replicate and interpret without my facilitation. In these smaller networks, they would have to know and continue the movement in a more private way.

I knew this moment. Even as a professional dancer I still cannot “pick up” choreography. I need time to orient myself if facings to the front change or I need time to feel it when different parts of the body are being employed. This activity was supposed to be accessible. However, accessible doesn’t just mean easier, it means equitable. How can one enter into a space on their own terms. It’s more about possessing the amount of information that breeds the most autonomy - knowing where the bathroom is located, how many steps to the bar, who surrounds me, and what movement quality are you really looking for - this knowledge combines with a personalized fortitude to make something inviting. As Lori and I talked, I reassured her that her autonomy was intact in the exercise. Still unsure, she would become an asset in another way. She would use her voice to describe and translate my movement during the event for everyone, making the choreography accessible and helping me transform access into an aesthetic. There’s tension in access because it can shift. When we approach access like art, it retains a form of care.

Image description: Participants take the floor, standing behind Jerron who’s center in front of the audience. Lori Hepner stands to the right of Jerron at the front, holding a microphone to announce the choreography to the room. Jerron’s right arm is extended out towards his right side, bent ever so slightly into a downward facing arc. The crowd follows his movements behind him, with a slew of arms extending outwards in the distance. As Jeron begins to lead the room through movements he announces, “In the centralized place, you don’t have autonomy. So what I’m going to do is take you through a piece of choreography that you’re going to have to take on and then we’ll figure out what happens next.”

With the crowd now dispersed into smaller circles, a DWC steward is captured interpreting Jerron’s choreography as her own now. She reaches her right arm outwards towards her right side, her torso and head follow accordingly. Behind her is a group of participants, each themselves interpreting the choreography without instruction. These are the smaller, decentralized networks, where the task remains to just interpret. Jerron guides them, stating: “when I say ‘go.’ you’re going to take on the same movement you just learned, and your intention is to imagine an invisible string that connects you all, and yet its not there. So from here, recreate the movement and see what happens.”

Image description: An older woman with orange tinted glasses, a blue sweater, and white hair stands in front of a group of other participants, holding a pink string with both hands in front of her. The string is part of a larger web, criss-crossing and tangling behind her. Introducing the element of string and the final phase of distribution, Jerron tells the audience, “In this configuration now, you’re going to speak to each other…with the choice of three phrases: ‘May I?’ ‘Can I’ and ‘I will.” In the distributed configuration, the intention is “to remain connected as you complete the choreography…but then also try and create connections that otherwise weren’t there the first time you tried this choreography.”

Image description: A diverse group of people look tenderly towards one another entangled in a web pink string. Some arms are raised upwards holding the string, some stay holding it closer to the body. Jerron affirms the group that at this point, “some of the choreography has gone out the window.” He also instructs them participants that “should they want to leave the network, you can.” In the distributed phase, audience members have autonomy over both their movements, and their participation in the choreography itself.

The exhilarating climax to this experience with the Distributed Web of Care occured when the majority of attendees stood to create the first large circle. In that moment I realized language, intention, inflection, body language, and space had communicated to them permission to be present and experience together. What did we do to get here? From my standpoint the prompts I gave came out of ways I usually felt connected. Simple and deep prompts, like place your head on your neighbor’s shoulder. Still, I was taken aback by their willingness to be vulnerable. In my mind I went back to the rehearsal even a few hours before when the stewards and I didn’t know how the large audience participation would settle in our bodies. We had gone through “feeling your own network” and had a semblance of what the smaller networks would entail. The larger circle was a great unknown. The scale was different: by rehearsal we had grown familiar with each other to warrant comfort to lean on someone’s shoulder, not so in the activation. I lovingly mentioned this with, “we didn’t have this in rehearsal!” There was a shorter, older woman next to me who delighted in being asked to lean or squeeze or participate. Her reaction was mine. The proceeding elements of play disbursed with glee as stewards wielded string and participants entangled themselves, as people closely observed disabled movement alongside a live audio description, and enjoyed a bespoke accompaniment.

Image description: Approximately 25 audience members participate in the scaffolding activity. They stand shoulder to shoulder next to one another, learning collectively towards the right side. Their heads and weight rest on the shoulder of the person to the right of them. Bound tightly together, the tilted configuration retains a steadiness and stability, marked by shared participation, trust, and care.

There is a group of people forever bound by a night at the Whitney. Within, the presentations and knowledge crept into their bodies, then their bodies creatively expressed minute or massive understanding of the new bits of knowledge, eventually creating an atmosphere that I thought symbolic of the content. Care is an action and we collectively built ourselves up through mutual understanding and joy to act carefully. I know everyone who attended the Distributed Web of Care event carries it with them.

I entered this activation striving to be worthy of a computational theorist only to realize that as much unlearning needs to occur as learning. I think when stewardship is invoked, an almost archaic word already, bringing notes of feudalism and lords, it calls on you to be similarly valorous. How? By true presence and presence alone.

Image description: A DWC Steward smiles jubilantly, with her eyes closed and arms raised above her as she holds onto the pink string, entangling behind her into the web of people. The image captures a moment of presence, focus, delight and trust.

About the Author:

Jerron Herman is an interdisciplinary artist who’s been featured with Heidi Latsky Dance at Lincoln Center, ADF, the Whitney Museum, and abroad in Athens. He’s been a principal member of HLD since 2011. Jerron now serves on the Board of Trustees at Dance/USA. Jerron has also shot for Tommy Hilfiger Adaptive, consulted for a Nike-sponsored project, and was profiled in Great Big Story. In 2018 he was a Snug Harbor PASS artist, a finalist for the inaugural Apothetae/Lark Play Development Lab Fellowship and was nominated for a Fellowship in Dance from United States Artists. His latest solos include Phys. Ed. and Relative – a crip dance party. Jerron studied at Tisch School of the Arts and graduated from The King’s College. The New York Times has called him, “…the inexhaustible Mr. Herman.”

Distributed Web of Care is an initiative to code to care and code carefully.

The project imagines the future of the internet and consider what care means for a technologically-oriented future. The project focuses on personhood in relation to accessibility, identity, and the environment, with the intention of creating a distributed future that’s built with trust and care, where diverse communities are prioritized and supported.

The project is composed of collaborations, educational resources, skillshares, an editorial platform, and performance. Announcements and documentation are hosted on this site, as well as essays by select artists, technologists, and activists.

-

Jun 30, 2024

에콜로지컬 퓨쳐스

-

Jun 30, 2024

Ecological Futures

-

Nov 26, 2022

P2P Residency Berlin

-

Jan 4, 2022

garden.local

-

Jun 7, 2020

Community Over Commodity

-

Mar 18, 2020

Oddkins

-

Oct 10, 2019

New Merchandise

-

Aug 10, 2019

Announcing Decentralized Networks Workshop

-

May 24, 2019

On Stewardship

-

May 23, 2019

Movement Scores

-

May 4, 2019

Who Owns the Stars: The Trouble with Urbit

-

May 1, 2019

Announcing WYFY School with BUFU

-

Mar 5, 2019

Announcing Lecture Performance at the Whitney Museum

-

Feb 25, 2019

Announcing Call for Deaf or Disabled Stewards

-

Feb 7, 2019

Making Space in Online Archives

-

Jan 29, 2019

Accessibility Dreams

-

Jan 28, 2019

Creative Self Publishing

-

Jan 11, 2019

Racial Justice in the Distributed Web

-

Dec 29, 2018

Announcing LACA Residency

-

Dec 28, 2018

Announcing DWC at Code Societies

-

Dec 21, 2018

Building a Museum 353 Years in the Future

-

Sep 11, 2018

Finding Intimacy within Black Feminist Criticism

-

Jul 26, 2018

still stuck with words

-

Jul 26, 2018

Distributed Dance Floor

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing Skillshares: Peers in Practice

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing the Distributed Web of Care Party

-

Jun 27, 2018

Communities and New Infrastructures

-

Jun 27, 2018

New Gardens

-

May 20, 2018

Announcing Summer 2018 Fellows

-

Apr 28, 2018

DWC Merchandise: Care Shirt & Hoodie

-

Apr 27, 2018

Announcing Artists in Residence at Ace Hotel New York

-

Apr 18, 2018

Documentation: Ethics and Archiving the Web

-

Apr 18, 2018

Call for Fellows and Stewards

-

Apr 17, 2018

Code of Conduct

-

Mar 18, 2018

About

-

Distributed Web of Care