Distributed Web of Care

Community Over Commodity

Community Over Commodity: Towards an Unselfish Care

by Adina Glickstein

The notion of “self care” has, unfortunately, proven no exception to contemporary capitalism’s all-encompassing drive to subsume and render profitable an ever-widening array of personal activities. What began as a radical intervention rooted in Black Feminst thought—Audre Lorde’s injunction to care for oneself as an act of “political warfare,” as she outlined it in Sister Outsider1—has since transmogrified into a chorus of market-based answers to the wider grievances of overwork and atomization, wrapped up in pastel packaging. In its current ubiquity, it’s easy to forget that the phrase “self-care” is a fairly recent addition to the common lexicon: the concept was popularized sometime around 2016, with search-engine hits peaking in the weeks after Donald Trump’s election to the office of US President.2 It indexes a common and understandable need—the desire to be delivered from the constant wear of workday weariness and chronic stress, currents of degradation that make us sick and sad, requiring rejuvenation. But has capital ever been known to overlook an opportunity to fold ever more activities into the realm of “productivity?”

The same neoliberal forces that heighten our need for caring intervention seek to commodify concern, packaging the prospect of “self-care” into consumable products and Instagram-ready ideologies. Body-positivity, which started as a liberation movement seeking to acknowledge fatphobia’s racist, colonialist underpinnings (explained in depth by Sabrina Strings3 and Caleb Luna4), is now a convenient way of selling underwear. Self-care sells, and under our current global circumstances—COVID-19 and its attendant pathologies of the mind and body, intense loneliness and spiking screen-time among them—one can easily slide into the delusion that buying “the right goods” is the only viable vector for self-expression. Our sense of ourselves recedes into that which can be signalled on-screen; paradoxically, as our awareness of our physical bodies wanes, our desire to accrue products promising self-improvement seems to skyrocket. Lived experience floats across digital space in fragments—what Hito Steyerl calls “junktime,”5 now reduced even further as physical presence is flattened into screen-mediation—both heightening our general distress and promising to fix it, if only we select the right skincare.

The obligation to publicly perform one’s physical and psychological upkeep has been a mainstay since at least the origin of capitalism: “technologies of the self,” per Foucault, are nothing new. But as our faith in market-based solutions only seems to grow—as “freedom” is increasingly understood to mean “unlimited consumer choice”—the radical politics that once underpinned “self-care” diminish in direct proportion to their utility for advertising purposes. As the logic of industrial production wanes and capital reinvents itself, opening new avenues to outrun the perpetually falling rate of profit, the extraction of attention becomes the new form of labor power.6 Searching for (and spending on) commodified self-care, then, collapses back into work’s seemingly never-ending dominion.

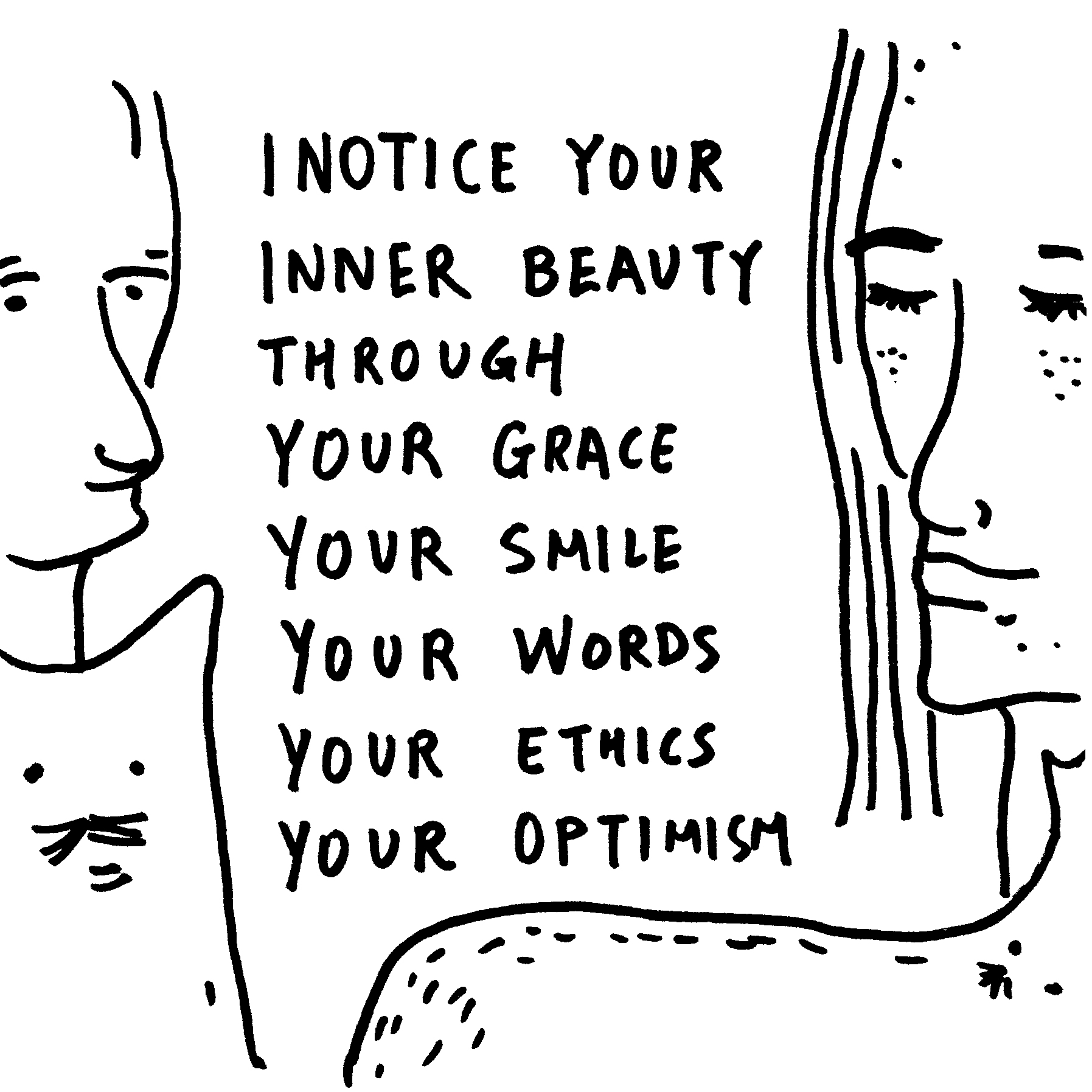

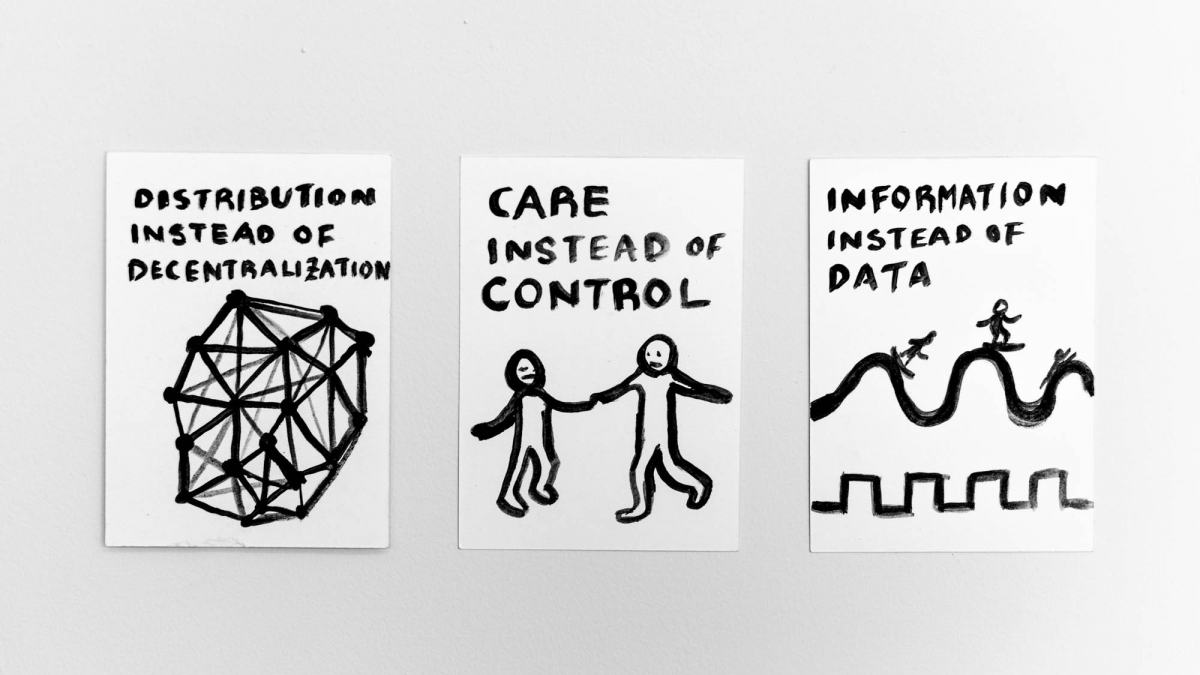

In his exhibition at Factory2 in Seoul, South Korea, “The Care of the Self: Journals and Letters,” Taeyoon Choi’s collected letters, drawings, and journal entries sketch a conscious alternative. The show comprises a series of intimate dispatches thoughtfully turned outward, constituting its viewing public through tender disclosure. In the last month, I have had the privilege of editing several of these texts as an assistant in Taeyoon’s studio, a member of his deeply collective practice and direct beneficiary of his time, care, and support. Touching topics from the protests in Hong Kong in 2019 to personal experiences of racism that have concerningly multiplied during the COVID-19 pandemic, from the mysteries of creative inspiration to the gift of intellectual kinship, Taeyoon’s drawings and writings allude to the possibility latent in true self-care—not what he calls “selfish care,” but a genuine and generous impulse to work on oneself in order to better serve the worlds we inhabit.

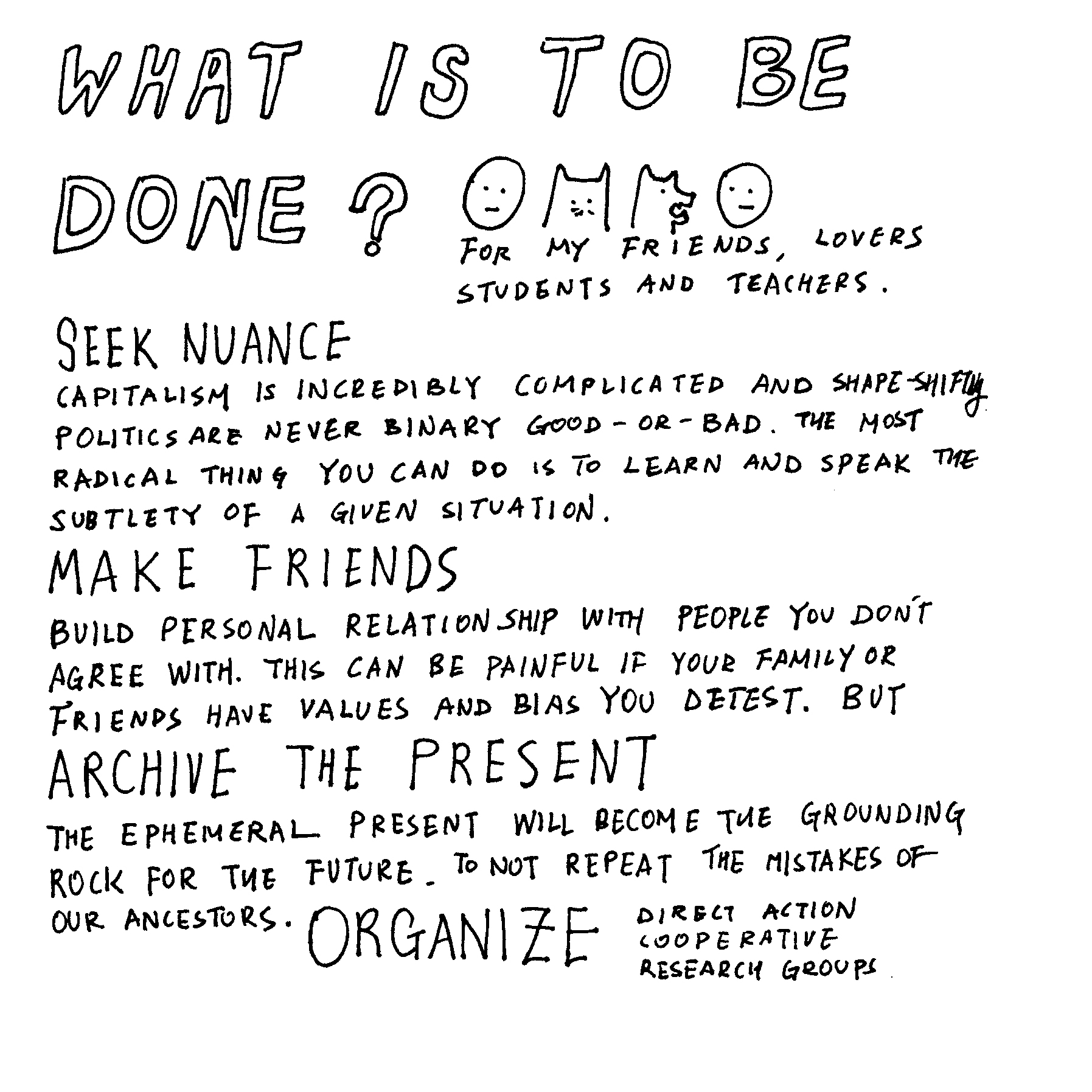

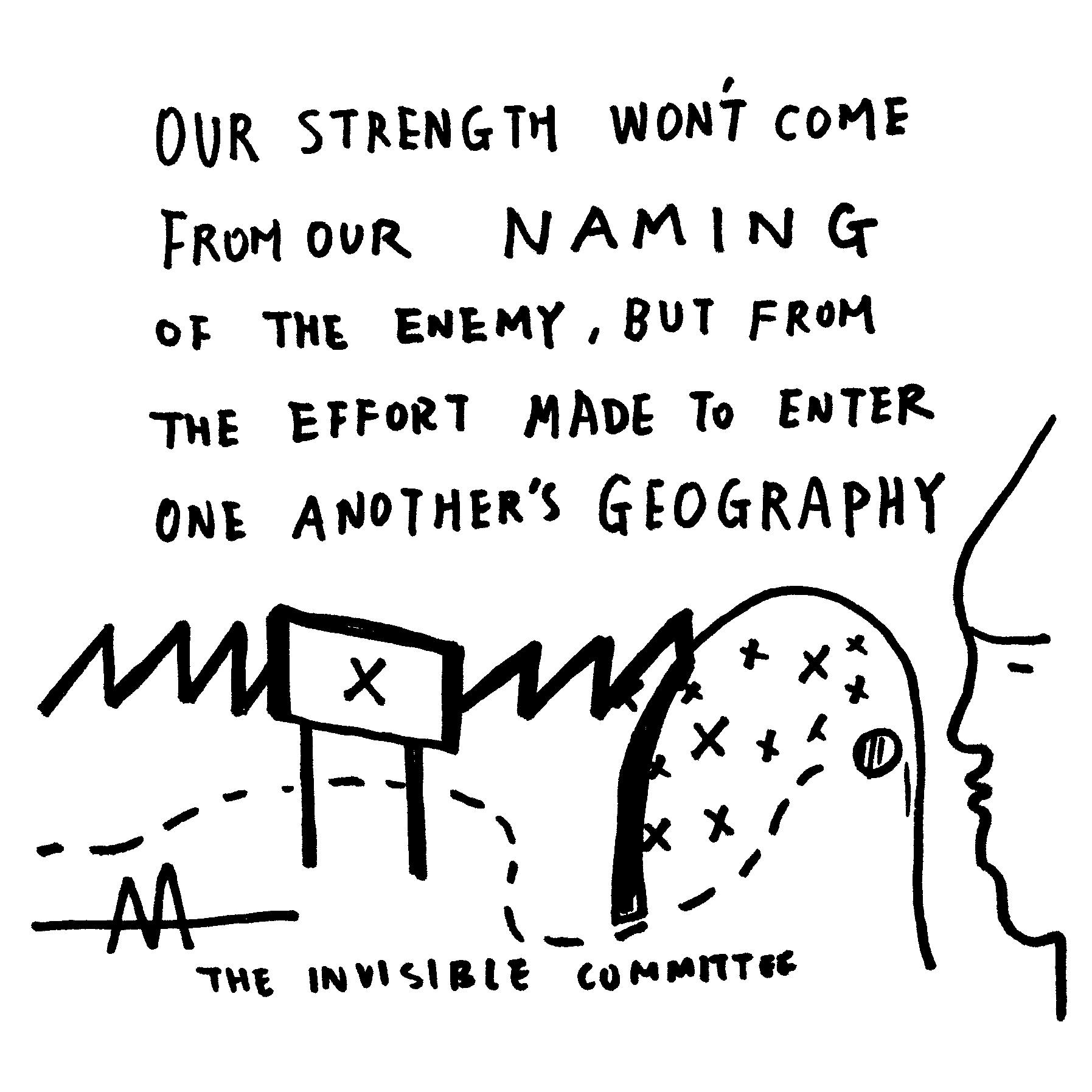

It’s precisely the genre of unselfish care, advocated across Taeyoon’s work, that demands our attention in these heightened times: “SEEK NUANCE,” he reminds us, encouraging the development of poetic approaches that make space for the nuanced self-reflection that enables us to do the necessary work: gently confronting our own culpability. “Artistic imagination…is a fragile force in a world filled with various hardness,” reads one drawing, reminding us that revolutionary action so often begins with an injunction against the crystallized, certain, or immutable. Solidarity can only exist when we learn to see past stasis—a process of unlearning the received un-wisdom that leads us to seek individual fulfillment over mutual support and collective becoming.

Sianne Ngai, in her exploration of “minor” affects, contends that cuteness, as a general aesthetic category, is fundamentally wrought with contradiction. In an interview for Cabinet Magazine, she explains how the category of “cute” does not facilitate cathartic action (as might, say, anger or unqualified joy), but rather, indexes a state of “suspended agency”—a diffuse, indefinite feeling that makes space for political ambiguity.7 It’s fitting, then, that Taeyoon’s aesthetic leaning is suffused with charm: delightful sketches animate his own poetics of contradiction, holding open the potential for collaborative imagination and insistence on an equitable future. Taeyoon’s particular heraldry of this aesthetic impulse—as opposed to, say, the pop-cuteness of “Pink Globalization”8-adjacent Hello Kitty aesthetics or the diminutive powerlessness that Ngai later cross-examines—stands in service of the profound importance of self-inquiry, mobilizing this potential for contradiction and transformation. The accessibility of his formal approach facilitates our entry into an ongoing reflective journey, inaugurating a process much more formidable than plopping into the proverbial bubble bath of selfish-care.

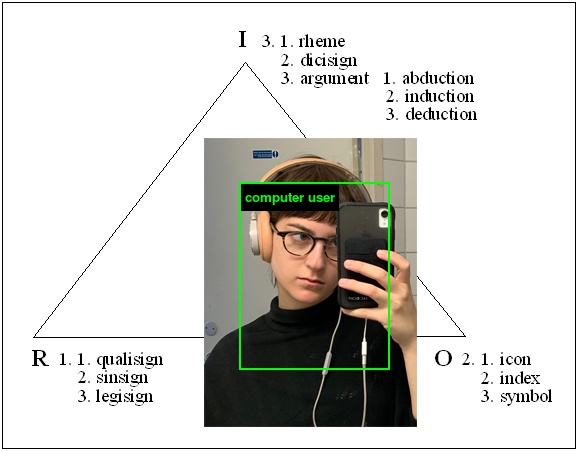

I first encountered Taeyoon from across the classroom during the School for Poetic Computation’s inaugural session of Code Societies in 2020, organized by Melanie Hoff with Neta Bomani and Emma Rae Norton. “Learning is an arduous act of repetition, staying humble and curious,” he read to my cohort from one of his letters.9 Here, he touched on something wider and more salient than simply the onerousness of learning how to code: “Unlearning,” he continued, “is to resist the atrocities of systemic oppression, violence formalized in the bureaucracies of knowledge production.” Another dimension of Taeyoon’s work—less foregrounded in this show but certainly present, stirring implicitly just below the surface of several sentiments on view—deals with computation and code, asking us to reflect on the ways in which human biases are cast back through technological mediation. How, he urged us to consider in Code Societies, does the conventional understanding of coding limit our real grasp on the myriad ways in which our experiences are coded—shaped by rules and mores that reinforce top-down cascades of power, typically unexamined and often to marginalized groups’ greatest detriment? His project here is crucial: it breaks down the distinction we have come to take for granted between the “passive” and the “programmers”: we are all, in a sense, always already coding, just as we are being coded by the instruments and systems that organize our movement through the world.10

Confronting our own positions in these toxic sedimentations is, inevitably, a challenge. The past few days, following George Floyd’s murder by US police officers, have been marked by heartening displays of activist solidarity against a background of state-sanctioned violence and racialized brutality. The conversations that have unfolded since then have repeatedly drawn my mind to the notion of “white fragility,” Robin DiAngelo’s term for white people’s inability to tolerate racial stress, so deeply is their—our—privilege both conditioned and expected.11 I struggle to write about it, my thoughts repeatedly muddied and undermined by my awareness of this privilege: I am a white American, a college graduate, generally unmarked as I move through the world. DiAngelo explains, though, that public-facing outpourings of white guilt and anger are antithetical to the necessary activist project at present: the unjust equilibrium can only begin to change when we overcome white fragility in favor of actively listening, relinquishing the urge to lead, and lending support. In his thoughtful approach to reframing self-care, Taeyoon offers each of us—viewers, humans, un-learners—a starting point for untangling these troubling trends within ourselves, attending to our needs as a passageway into foregrounding those of others.

“The Care of the Self” is a means towards decentering the self, situating one’s own being within a broader community and stabilizing ourselves against the deleterious capitalist customs—individualization among them—that fragment us, foreclosing the possibility of solidarity and revolutionary change. He approaches this conversation with patience and generosity, staging an accessible point of entry into that onerous process of unlearning, the discomfort of which we must be responsible enough to contend with each day forward. “What distinguishes humans from machines,” he explains in a comic entitled “WHAT IS TO BE DONE?”, “is our capacity for sympathy.” This is the capacity that his work explicitly draws upon, gracefully activating our ability to move into unlearning—pushing us to call forth a more caring world, wrought nonetheless with delicious nuance and uneasy contradiction. Unlearning as unworking: Taeyoon models how this process of untangling is an act of calculated counter-productivity, highlighting the demand for constant output and pausing to proceed otherwise. What if, instead of perpetually building towards the new, we re-dedicated ourselves and our resources towards reflection, towards a break from the logic of “customer” and “creative producer,” moving instead in the direction of commonality and care?

About the Author

Adina Glickstein is a critic and research-driven multidisciplinary artist. Their art practice, which spans video, installation, and text-based work, examines the attention economy and the historical relationship between cinema and labor. Their writing has appeared in Artforum, Spike Art Quarterly, Flash Art, and Hyperallergic. They also work as an assistant at Taeyoon Studio.

Original drawings by Taeyoon Choi

-

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007. ↩

-

Kisner, Jordan. “The Politics of Conspicuous Displays of Self-Care.” The New Yorker, 14 March 2017. Accessed June 1 2020. ↩

-

Strings, Sabrina. Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fatphobia. New York: NYU Press, 2019. ↩

-

Luna, Caleb. “Ep. 217: Caleb Luna - Race, Class, and the Fat Body.” Woman of Size with Jana Schmieding. June 17 2019. ↩

-

Steyerl, Hito. “The Terror of Total Dasein: Economies of Presence in the Art Field.” DIS Magazine. Accessed June 1 2020. ↩

-

Beller, Jonathan. The Cinematic Mode of Production. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. ↩

-

Jasper, Adam, and Sianne Ngai. “Our Aesthetic Categories: An Interview with Sianne Ngai.” Cabinet Magazine, Issue 43. Accessed June 1 2020. ↩

-

Yano, Christine Reiko. Pink Globalization: Hello Kitty’s Trek Across the Pacific. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013. ↩

-

Choi, Taeyoon. “Unlearning.” A letter to Code Societies students. Jan 6 2020. Accessed June 1 2020. ↩

-

Hoff, Melanie. “Code Societies Orientation.” Lecture. The School for Poetic Computation, New York, NY. Jan 6 2020. ↩

-

DiAngelo, Robin. “White Fragility.” International Journal of Critical Pedagogy vol. 3, 2011. ↩

Distributed Web of Care is an initiative to code to care and code carefully.

The project imagines the future of the internet and consider what care means for a technologically-oriented future. The project focuses on personhood in relation to accessibility, identity, and the environment, with the intention of creating a distributed future that’s built with trust and care, where diverse communities are prioritized and supported.

The project is composed of collaborations, educational resources, skillshares, an editorial platform, and performance. Announcements and documentation are hosted on this site, as well as essays by select artists, technologists, and activists.

-

Jun 30, 2024

에콜로지컬 퓨쳐스

-

Jun 30, 2024

Ecological Futures

-

Nov 26, 2022

P2P Residency Berlin

-

Jan 4, 2022

garden.local

-

Jun 7, 2020

Community Over Commodity

-

Mar 18, 2020

Oddkins

-

Oct 10, 2019

New Merchandise

-

Aug 10, 2019

Announcing Decentralized Networks Workshop

-

May 24, 2019

On Stewardship

-

May 23, 2019

Movement Scores

-

May 4, 2019

Who Owns the Stars: The Trouble with Urbit

-

May 1, 2019

Announcing WYFY School with BUFU

-

Mar 5, 2019

Announcing Lecture Performance at the Whitney Museum

-

Feb 25, 2019

Announcing Call for Deaf or Disabled Stewards

-

Feb 7, 2019

Making Space in Online Archives

-

Jan 29, 2019

Accessibility Dreams

-

Jan 28, 2019

Creative Self Publishing

-

Jan 11, 2019

Racial Justice in the Distributed Web

-

Dec 29, 2018

Announcing LACA Residency

-

Dec 28, 2018

Announcing DWC at Code Societies

-

Dec 21, 2018

Building a Museum 353 Years in the Future

-

Sep 11, 2018

Finding Intimacy within Black Feminist Criticism

-

Jul 26, 2018

still stuck with words

-

Jul 26, 2018

Distributed Dance Floor

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing Skillshares: Peers in Practice

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing the Distributed Web of Care Party

-

Jun 27, 2018

Communities and New Infrastructures

-

Jun 27, 2018

New Gardens

-

May 20, 2018

Announcing Summer 2018 Fellows

-

Apr 28, 2018

DWC Merchandise: Care Shirt & Hoodie

-

Apr 27, 2018

Announcing Artists in Residence at Ace Hotel New York

-

Apr 18, 2018

Documentation: Ethics and Archiving the Web

-

Apr 18, 2018

Call for Fellows and Stewards

-

Apr 17, 2018

Code of Conduct

-

Mar 18, 2018

About

-

Distributed Web of Care