Distributed Web of Care

Oddkins

by Taeyoon Choi

Oddkin is a word Donna Haraway uses to describe an unlikely collection of intimate people. In ‘From Cyborgs to Companion Species,’ a lecture Haraway delivered on September 13, 2003 at the University of Berkeley, she unpacks the concept through various stories and metaphors. I’m fascinated by the word oddkin. The word captures the expansive and intimate relationships I have in my personal life, at my work in the School for Poetic Computation, and in the Processing community. I’m bilingual, so it’s natural for me to translate a new word into Korean. The word kin is 친척 (親戚 in Chinese), a family member. I couldn’t find the Korean translation of oddkin. I asked my Twitter followers if anyone would help translate it, and media artist Masayuki Akamatsu suggested 기묘한동류(妙な同類 in Japanese). It doesn’t have the earthy, crittery feel of oddkin, but it contains the sense of unlikely intimacy. It’s close enough.

Dear oddkins. I’ve been lucky to participate and help the p5.js contributors conference at the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry in 2015 and remain a member of the project. p5.js is a JavaScript library for creative coding, with a focus on making coding accessible and inclusive for artists, designers, educators and beginners. Artist and founder of p5.js, Lauren McCarthy asked me to write a piece for the p5.js zine in early 2020. In this letter, I take an opportunity to think about you, my oddkins in the world of art, technology and education, and share a list of questions for you.

I’d like to challenge the misuse of the word “democracy” in the context of technology. “Democracy” implies distributed power, fair representation, and equity for every citizen in a society. In conferences or demo days, I will often hear someone say that they are trying to ‘democratize’ technology by making tools or resources. For example, “I made this open-source tool. Now everyone can do what I do!” What they are not saying, and the privilege they are ignorant of, is that in order to use the tool you need to be technically fluent, be in an environment where you are accepted as a technical person, and have access to computers and network. In reality, technology, tools and resources alone cannot uphold democracy. Truly democratic societies require ongoing maintenance, stewardship and education. The question of who’s considered a citizen of society remains in every democratic system. Thus, the question of democracy is essentially a question of personhood– who is visible, whose labor is valued and who is heard in space.

What the p5.js project does differently, and has from the beginning, is demystify the common narrative of a lone engineer creating a powerful framework and the stereotypes of who’s seen as technical and/or artistic. p5.js is a community where contributions from QTPOC, non-binary, disabled and Deaf, and non-technical individuals are valued equally. The p5.js community is definitely more woke than most other software communities, but it is also a truer reflection of the reality of software/hardware development. There are almost always non-technical and non-traditional contributors who are integral to the success of any technology. They include but are not limited to writers, educators, testers, designers, Quality Control professionals and service workers.

The questions of whiteness in the open source field remains unresolved for me. I’ve attended numerous software and hardware conferences over the years. Some were highly exclusive and self-selective, others were open and inviting to newcomers. In the U.S. and Europe, the conference speakers and attendees were dominatingly white males. In Asia, I noticed the conference organizers and attendees trying to replicate white supremacy, tech solutionism, and patriarchy with a bit of nationalism. Codes of Conduct did not exist in major tech spaces until a few years ago. I could write a book about the troubling experiences I have had and witnessed in tech conferences. Older, established, white male engineers and academics making rude comments to female, gender non-conforming, people of color, may need to be divvied up into a few chapters. Young tech dudes promising to solve the world’s greatest challenges with code. Introverts who are actually just snobbish, escaping to their devices to avoid human contact, yet stalking women with overt confidence. The most insidious forms of racism happen offstage. How a speaker badge isn’t enough for a person of color to enter the speakers’ lounge, how white bartenders treat a black person with offhand racist jokes, how women of color are tokenized for photo opportunities and a shout out on a diversity statement. They can get a chapter of their own in my book about tech conferences.

To survive in white spaces as a person of color, I learned to adapt to the expectations of others. In other words, I learned to play the white man’s game. Once I felt grounded, I leveraged my place to give voice to the others. Speaking my truth made some people uncomfortable and I lost some opportunities. Speaking up brought me the respect of others, especially those who want to use their power in white spaces to bring changes.

How to speak up to challenge the establishment? I think nuance and candor are essential to start a conversation. No one likes to be criticized, but everyone loves to be understood. When I was learning to code, a friend told me, “Treat your computer like your younger sibling.” During the p5.js Contributors Conference, Jason Alderman, Tega Brain, Luisa Pereira and I created ‘Debugging guide for p5.js.’ This approach of care, patience and play is essential in exploratory and poetic computing. I think a similar approach is necessary to navigate the technology industry and community. When someone makes a mistake, call them out, but don’t cancel them out. Give them a humane error message: Hi there. You’ve done something that made me feel uncomfortable. It doesn’t mean you are a bad person. May I suggest how your behavior can be improved? Give them a second chance. If they improve, great! If they continue to make the same mistake, move on. That is the labor of care in a technological society.

Media and design researcher Shannon Mattern’s essay “Maintenance and Care,” published in Places Journal in November 2018, offers “a working guide to the repair of rust, dust, cracks, and corrupted code in our cities, our homes, and our social relations.” Mattern connects care-work in relation to the practice and concept of maintenance to reveal that “the distinctions between these practices are shaped by race, gender, class, and other political, economic, and cultural forces.” Inspired by her provocation, I want to ask some questions regarding the maintenance of technology and the tech industry. How can we distinguish between humane, unintentional errors within the systems of oppression that make a global impact? How can we scale the practice of care to a global network of solidarity towards social and environmental justice?

Should we train machine learning algorithms with a better data set to be less biased? Or should we not train the machines if the algorithms can be appropriated for malicious uses? If current algorithms contain biases of white male engineers, should POC engineers train machine learning algorithms to be more inclusive of their data and perspectives? Unlearning the biases we’ve been taught and undoing wrong are very difficult. Things get complicated, especially regarding restorative justice in the context of a Capitalist society. When we cooperate with those who’ve committed social ill in the past, what is the real cost of their redemption? By greenwashing, diversity-washing and care-washing, are we maintaining a system of injustice? Sure, no money is clean, but we decide how to get it. The conversation about ethical grayscale is highly contextual, but are there some things that are just wrong and should not be tolerated? If the true meaning of care is to take responsibility, are there some things that must be divided through binary determinism? In other words, are there some people or organizations we should not consider working with at all?

I’m struggling to come to terms with these questions, my oddkins. The distinction between what is ethical and unethical seems blurry, while technology is used to create greater disparities between those who have wealth, power and resources and those who don’t. The reason I’m attracted to the word and idea of oddkin is that it mends contradictions (oddness) with intimacy (kinship). If we consider ourselves, developers, users and educators of p5.js as an example for an alternative technological community, what can we offer to the greater world? Should we maintain a system that’s unfairly designed? Should we start a new system?

I kindly ask if we can think about the question of care in relation to independence (autonomy) and interdependence (kinship). I’m interested in hearing from my oddkins.

Distributed Web of Care is an independent publishing project. Please support us via tax-deductible donation at the OpenCollective.

Written by Taeyoon Choi, February, 2020, Published in March 18, 2020

Illustration by Taeyoon Choi for Getting Started with p5.js published by O’Reilly

Edited by Shea Fitzpatrick

Special thanks to Shannon Mattern, Lauren McCarthy, Dorothy Santos, Masayuki Akamatsu, Mizuki Takeshita and the Centre for Heritage and Textile, Golan Levin and the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry and Saerom Suh.

Taeyoon Choi is an artist, educator, and organizer. He is a cofounder of the School for Poetic Computation, an artist-run institution with the motto of “More Poetry, Less Demo!” Taeyoon seeks a sense of gentleness, intellectual kinship, magnanimity, justice and solidarity in his work and collaboration. He has presented installations, performances and workshops at Eyebeam Art and Technology Center, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, New Museum, M+ Museum, Istanbul Design Biennale, Seoul Mediacity Biennale and Venice Biennale for Architecture. He contributed to alternative education such as the Public School New York, Occupy University and Triple Canopy Publication Intensive. Recently, Taeyoon worked with Mimi Onuoha to start the New York Tech Zine Fair. He collaborated with Nabil Hassein and Sonia Boller to organize the Code Ecologies conference about the environmental impact of technology. As a disability justice organizer, Taeyoon continues to work with the Deaf and Disability community towards accessibility and inclusion.

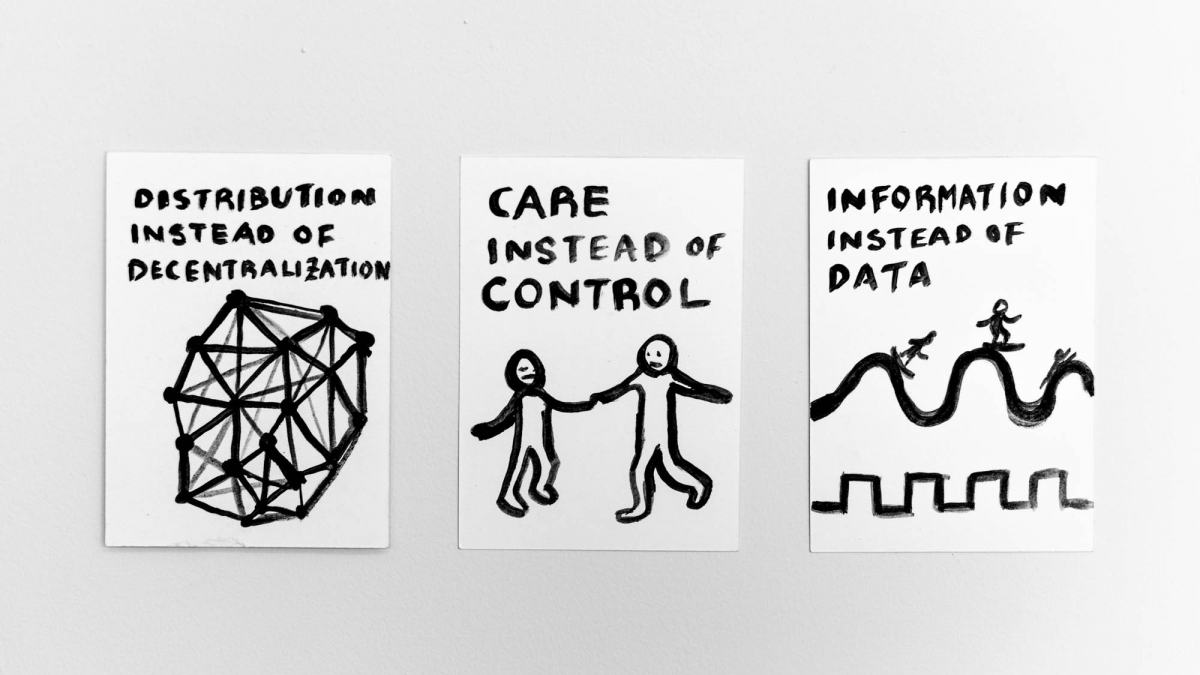

Distributed Web of Care is an initiative to code to care and code carefully.

The project imagines the future of the internet and consider what care means for a technologically-oriented future. The project focuses on personhood in relation to accessibility, identity, and the environment, with the intention of creating a distributed future that’s built with trust and care, where diverse communities are prioritized and supported.

The project is composed of collaborations, educational resources, skillshares, an editorial platform, and performance. Announcements and documentation are hosted on this site, as well as essays by select artists, technologists, and activists.

-

Jun 30, 2024

에콜로지컬 퓨쳐스

-

Jun 30, 2024

Ecological Futures

-

Nov 26, 2022

P2P Residency Berlin

-

Jan 4, 2022

garden.local

-

Jun 7, 2020

Community Over Commodity

-

Mar 18, 2020

Oddkins

-

Oct 10, 2019

New Merchandise

-

Aug 10, 2019

Announcing Decentralized Networks Workshop

-

May 24, 2019

On Stewardship

-

May 23, 2019

Movement Scores

-

May 4, 2019

Who Owns the Stars: The Trouble with Urbit

-

May 1, 2019

Announcing WYFY School with BUFU

-

Mar 5, 2019

Announcing Lecture Performance at the Whitney Museum

-

Feb 25, 2019

Announcing Call for Deaf or Disabled Stewards

-

Feb 7, 2019

Making Space in Online Archives

-

Jan 29, 2019

Accessibility Dreams

-

Jan 28, 2019

Creative Self Publishing

-

Jan 11, 2019

Racial Justice in the Distributed Web

-

Dec 29, 2018

Announcing LACA Residency

-

Dec 28, 2018

Announcing DWC at Code Societies

-

Dec 21, 2018

Building a Museum 353 Years in the Future

-

Sep 11, 2018

Finding Intimacy within Black Feminist Criticism

-

Jul 26, 2018

still stuck with words

-

Jul 26, 2018

Distributed Dance Floor

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing Skillshares: Peers in Practice

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing the Distributed Web of Care Party

-

Jun 27, 2018

Communities and New Infrastructures

-

Jun 27, 2018

New Gardens

-

May 20, 2018

Announcing Summer 2018 Fellows

-

Apr 28, 2018

DWC Merchandise: Care Shirt & Hoodie

-

Apr 27, 2018

Announcing Artists in Residence at Ace Hotel New York

-

Apr 18, 2018

Documentation: Ethics and Archiving the Web

-

Apr 18, 2018

Call for Fellows and Stewards

-

Apr 17, 2018

Code of Conduct

-

Mar 18, 2018

About

-

Distributed Web of Care