Distributed Web of Care

Finding Intimacy within Black Feminist Criticism

by Jessica Lynne, DWC Arist In Residence

(an evolving statement first commissioned by the Milwaukee Artist Resource Network in 2017)

Jessica Lynne, on the left with ARTS.BLACK partner, Taylor Aldridge. Photo: Ash Arder.

I have been spending time with Barbara Smith’s essay, “Towards a Black Feminist Criticism.” A lot of time, actually. It has become a central point of reference for me recently as I’ve worked to get to the root of my impulses as an art critic.

Long before I tried to write this I felt I was attempting to do something unprecedented, something dangerous…

In 1978, Smith is working towards an impossibility, as she describes, that aims to render visible, through criticism, the literature of Black women writers, especially Black lesbian writers. How does one move against silence(s)? How has the literature of Black women not been served by the larger apparatus of literary criticism (For Smith: white male critics, Black male critics, white woman critics who think of themselves as feminists)? For her part then, Smith puts forth a methodology—the how— that takes seriously the entanglement of race, class, and the politics of sex in any effort to understand the subtleties of Black women’s writing. I like to imagine the following question as subtext: through what lens do you attend to the work of Black women?

In 1978, I also imagine Smith arguing that even before we get to the how, we must first acknowledge another inquiry: do you attend to the work of Black women? Here I am, almost 40 years after the publishing of this essay feeling like I gotta carry Smith with me at all times as I set priorities for myself.

I am often asked: who are you writing for? This question is typically followed by: why do you write? To employ a praxis of Black feminist criticism means that I write to place care around the practices of Black women artists. Their work. Their archives. Their fullness.

Criticism, then, is a way of showing up. It is a way of placing intellectual frameworks around the gestures and processes of artists. It is a way of preventing gaps and exclusions. What is most urgent for me now is engaging in a critical practice that moves against silences and undertakes assessments of visual, performance, and literary culture in a manner that centers and prioritizes the complexities of black womanhood(s).

Black feminist criticism would by definition be highly innovative, embodying the daring spirit of the works themselves.

Earlier this year, I was in a room full of Black women artists, friends of mine, discussing our big dreams and expressing our big frustrations. “Who is going to do the real thinking about us,” one friend began, “most of this writing is fluff shit.” I nodded my head in agreement. That she made a distinction between the real and the fluff didn’t surprise me. The fluff: surface level analysis, press release regurgitation. The real: deep level, nuanced meditations. “I’m not sure the market is interested in that type of art criticism,” I say. “We’re all writing the same things about the same artist because it’s profitable. It’s a numbers game.”

“We need a new criticism then,” this friend says.

She’s right.

On the one hand, it is true that the job of the critic is to respond in real time. That if an exhibition or gallery show is on view for, let’s say, four months, a strong and early review can be leveraged by an artist for future opportunities. This is especially true for emerging artists (a precarious term but one I will use for the sake of this essay). I will contend here that a strong piece of criticism is not merely one that lauds an artist. It is also a text that contextualizes, proposes new questions, and insightfully articulates what is working and what is not working. On the other hand, as newspapers and magazines shutter their arts coverage and more and more of us cobble together livelihoods from freelance writing or write in addition to full-time jobs ( I am one of these people), it is also true that what is lacking is both time and presence.

That when my friend calls for a “new criticism” she is calling for a new way by which critics form a relationship to her work. This is to say that, perhaps, a Black Feminist criticism offers a space for this new relationship, one that dares me to slow down and make space for intimacy.

I only hope that this essay is one way of breaking our silence and our isolation, of helping us to know each other.

I am a Black woman critic maturing alongside Black women artists. I conduct studio visits with them. I go to their openings and talks and panels. We have our group chats and email threads. They are my peers and colleagues and sounding boards.

Our exchanges, formal and informal, constitute a necessary, generative meeting point in which we might challenge, provoke, and support one another. I’m not entirely convinced my eye is compromised because of this proximity though such is the argument with which I wrestle. We are women coming from the peripheries and we are seeing one another and we are holding on to one another and we are holding one another accountable. I guess what I’m trying to say is that maybe (art) criticism should also make space for the rigor that can arise when we orient ourselves horizontally. What does criticism look like when we reject the myth that it can only manifest itself in one way? I want to propose that intimacy in criticism serves both a political and aesthetic purpose as it moves us closer to planes of formal experimentation (as in, how does your criticism show up on the page) while allowing for a sustained close reading of a body of work as it unfolds over time in other words, an investment.

Just as I did not know where to start, I am not sure how to end. I feel that I have tried to say too much and at the same time have left too much unsaid.

I’ll probably return to Smith a few more times before the year ends. Criticism is not static. There is much left to learn. And so, this feels less like an ending and more a righteous beginning.

About the Author:

Jessica Lynne is a Brooklyn-based writer and art critic. She is co-founder and editor of ARTS.BLACK, a journal of art criticism from Black perspectives. Find her online at @lynne_bias.

Jessica Lynne is a Brooklyn-based writer and art critic. She is co-founder and editor of ARTS.BLACK, a journal of art criticism from Black perspectives. Find her online at @lynne_bias.

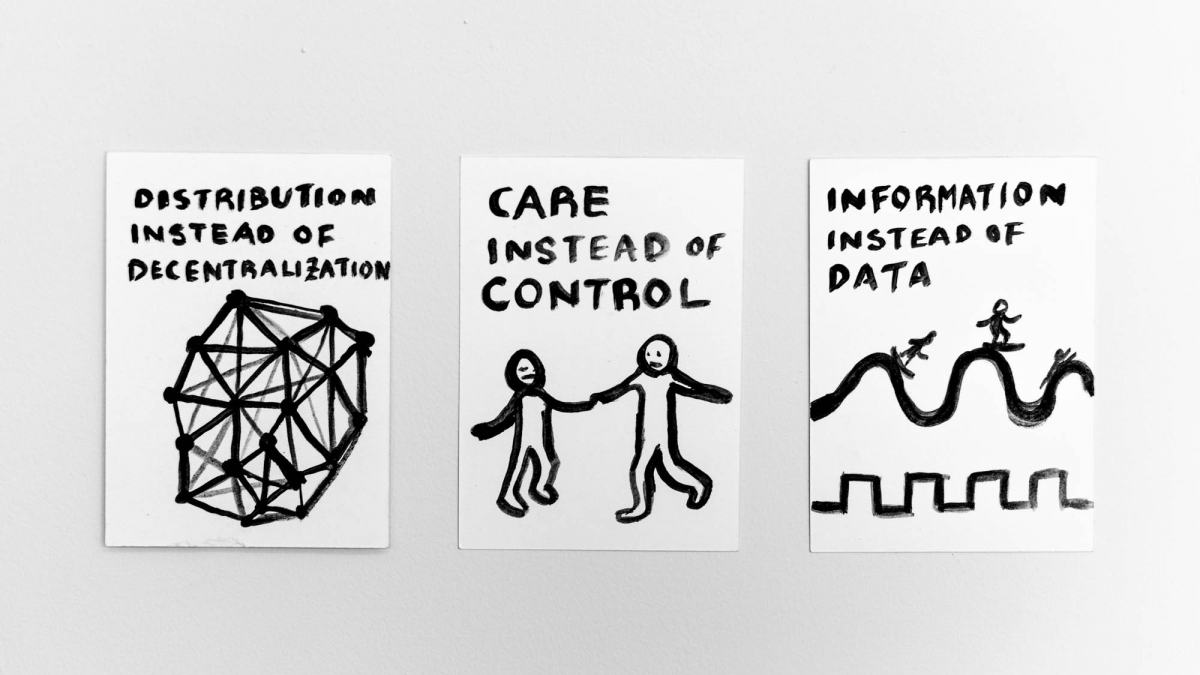

Distributed Web of Care is an initiative to code to care and code carefully.

The project imagines the future of the internet and consider what care means for a technologically-oriented future. The project focuses on personhood in relation to accessibility, identity, and the environment, with the intention of creating a distributed future that’s built with trust and care, where diverse communities are prioritized and supported.

The project is composed of collaborations, educational resources, skillshares, an editorial platform, and performance. Announcements and documentation are hosted on this site, as well as essays by select artists, technologists, and activists.

-

Jun 30, 2024

에콜로지컬 퓨쳐스

-

Jun 30, 2024

Ecological Futures

-

Nov 26, 2022

P2P Residency Berlin

-

Jan 4, 2022

garden.local

-

Jun 7, 2020

Community Over Commodity

-

Mar 18, 2020

Oddkins

-

Oct 10, 2019

New Merchandise

-

Aug 10, 2019

Announcing Decentralized Networks Workshop

-

May 24, 2019

On Stewardship

-

May 23, 2019

Movement Scores

-

May 4, 2019

Who Owns the Stars: The Trouble with Urbit

-

May 1, 2019

Announcing WYFY School with BUFU

-

Mar 5, 2019

Announcing Lecture Performance at the Whitney Museum

-

Feb 25, 2019

Announcing Call for Deaf or Disabled Stewards

-

Feb 7, 2019

Making Space in Online Archives

-

Jan 29, 2019

Accessibility Dreams

-

Jan 28, 2019

Creative Self Publishing

-

Jan 11, 2019

Racial Justice in the Distributed Web

-

Dec 29, 2018

Announcing LACA Residency

-

Dec 28, 2018

Announcing DWC at Code Societies

-

Dec 21, 2018

Building a Museum 353 Years in the Future

-

Sep 11, 2018

Finding Intimacy within Black Feminist Criticism

-

Jul 26, 2018

still stuck with words

-

Jul 26, 2018

Distributed Dance Floor

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing Skillshares: Peers in Practice

-

Jun 27, 2018

Announcing the Distributed Web of Care Party

-

Jun 27, 2018

Communities and New Infrastructures

-

Jun 27, 2018

New Gardens

-

May 20, 2018

Announcing Summer 2018 Fellows

-

Apr 28, 2018

DWC Merchandise: Care Shirt & Hoodie

-

Apr 27, 2018

Announcing Artists in Residence at Ace Hotel New York

-

Apr 18, 2018

Documentation: Ethics and Archiving the Web

-

Apr 18, 2018

Call for Fellows and Stewards

-

Apr 17, 2018

Code of Conduct

-

Mar 18, 2018

About

-

Distributed Web of Care